CONTENTS

Chapter 1 – THE NEW AGE

Chapter 2 – QUIMBY THE PIONEER

Chapter 3 – QUIMBY’S METHOD OF HEALING

Chapter 4 – THE FIRST AUTHOR

Chapter 5 – THE BEGINNINGS OF CHRISTIAN SCIENCE

Chapter 6 – THE MENTAL SCIENCE PERIOD

Chapter 7 – THE NEW THOUGHT

Chapter 8 – THE FIRST ORGANIZATIONS

Chapter 9 – THE FIRST CONVENTIONS

Chapter 10 – THE INTERNATIONAL NEW THOUGHT ALLIANCE

Chapter 11 – OTHER ORGANIZATIONS

Chapter 12 – THE MOVEMENT IN FOREIGN LANDS

Chapter 13 – LOOKING FORWARD

Chapter 14 – KINDRED MOVEMENTS

APPENDIX

Chapter 1 – THE NEW AGE

THE Great War came as a vivid reminder that we live in a new age. We began to look back not only to explain the war and find a way to bring it to an end, but to see what tendencies were in process to lead us far beyond it. There were new issues to be met and we needed the new enlightenment to meet them. The war was only one of various signs of a new dispensation. It came not so much to prepare the way as to call attention to truths which we already possessed. The new age had been in process for some time. Different ones of us were trying to show in what way it was a new dispensation, what principles were most needed. What the war accomplished for us was to give us a new contrast. As a result we now see clearly that some of the tendencies of the nineteenth century which were most warmly praised are not so promising as we supposed.

We had come to regard the nineteenth century as the age of the special sciences. We looked to science for enlightenment. We enjoyed new inventions without number, such as the steam-engine, the electric telegraph, the telephone, and our life centered more and more about these. But the nation having most to do with preparation for the war was the one which made the greatest use of the special sciences. Modern science was in fact materialized for the benefit of a military party. As a result of our study of the war many of us are now more interested in higher branches of knowledge than in the special sciences. We insist that science is for use, and we reserve the right to say what that use shall be. We have lost interest in science not explicitly employed for moral ends.

Again, we called attention to the nineteenth century with great pride as the age of the philosophy of evolution. We put our hopes in that philosophy. We expected it to explain the great mysteries. We wrote history anew, we issued new text-books, and in a thousand ways adapted our thought to the great idea of gradual development. But while the new philosophy accomplished wonders for us in so far as it showed the reign of law, the uniformity of nature, the immanence of all causality, it deprived us of our former belief in the divine purpose. Taken literally, it led us to regard nature as self-operative. We had to work our way back to the divine providence. We realized that evolutionism was simply a new form of materialism. We carried forward from the nineteenth century into the twentieth many great problems of life and mind not yet solved. The philosophy of evolution has come to stay, but not even in the form of Bergson’s interpretation is it satisfactory.

We also looked upon the nineteenth century as the period of development of idealism. The modern movement, beginning in Germany, spread to England and the United States, and we witnessed a most interesting form of it in our transcendentalism. This movement, in brief, emphasized Thought as the cardinal principle. It sought to explain all things by reference to this Thought. It found the starting-point as well as the meaning in the Idea, The outward world was regarded as a mere phenomenon in comparison. This movement had permanent contributions to make to our thought. We associate the name of Emerson with its spiritual meanings. But most of its theoretical teachings seem far removed from our practical thought today. We no longer try to spin the world out of the mere web of Thought. We need a new idealism to replace that of Fichte and Hegel. We are suspicious of mere speculation. The idealism of the last century is already mere matter of history.

The nineteenth century was also the epoch of religious liberalism. Throughout the century Unitarianism accomplished a great work. The liberalizing tendencies spread into all denominations. We take many ideas as matters of course nowadays for which the great leaders of the time of Theodore Parker and James Martineau had to contend at the risk of intellectual martyrdom The liberalism of the early part of the century had a destructive work to do before the freer thought of the day could assimilate the teachings of modern science and give us our present constructive faith. It requires decided effort on our part today to put ourselves back to the time when narrowing dogmas still ruled the human mind, when it was customary to pray for divine intervention, to believe in miracles as infractions of law, and to draw lines of rigid exclusiveness around the ecclesiastical sect to which one happened to belong. The history of liberalism is so comprehensive that it is always a question nowadays what we mean when we use the term. To be liberal is to be of the new age. The real question is, what is the goal of liberalism? The answer which a disciple of the New Thought would give should be understood in the light of a long struggle for the right to employ mental healing, a struggle which went on almost apart, independently of the warfare waged by Unitarianism upon the old doctrines and dogmas.

As in the case of the philosophy of evolution, we have had religious liberalism long enough with us to realize that it has a sting to it. For the less enlightened, the smaller minds among liberals, freedom of religious thought developed according to the tenets of the new or higher criticism imported from Germany. Undertaking to explain how the Bible came into being, with the variations and errors of texts, the imperfections of language, the conflict of opinions due to the fact that the books of which the Bible consists were brought together by other hands long after the supposed writers flourished, the critics proved too much and exemplified a habit of judging by the letter. Biblical criticism became destructive and had much to do with the weakening of faith still apparent among us. If we say that the new age is the epoch of belief in the spiritual meaning of the Scriptures, we must qualify it by saying that the greater work remains to be done. Devotees of the New Thought have freely interpreted the Bible for themselves.

What is needed is a spiritual science of interpretation to offset the destructive work which the age accepted without knowing what it believed.

The great century that has passed also witnessed the coming of spiritism in its modern form. In retrospect we are now able to say that behind all that was misleading in the new movement there were certain great truths which the world needed. Old ideas of death have been overcame, the spiritual world has been brought nearer, and larger views of the human spirit have been generally accepted. Out of the new interest came psychical research as an endeavor to put the phenomena of the whole field of spiritism on a scientific basis. The results have been meager and slowly attained. But the movement has been educational. Its positive results are discoverable in what we have been led to think. Although the whole field lies somewhat apart from that of the New Thought, the mental-healing movement has profited by it. Spiritualism is a protest against the materialism of the nineteenth century. It is one of the signs of the times. We have been gradually coming to know what spirit-return means, what a genuine message from the other life would be. What we want is a better philosophy than that which psychical experiences ordinarily seem to imply.

Psychology in the sense in which we now employ the term did not exist when the New Thought movement began. We are now so accustomed to the psychological point of view of every subject of public interest that we forget how recent it is. Modern science in general had to come first, then the theory of evolution, with the attempt to explain mental life on a biological basis, and the gradual transfer of interest to the inner life. The terms “suggestion,” “subconscious,” and the other words which we employ so freely are very new indeed. The old intellectualism in psychology prevailed for the most part throughout the nineteenth century. When a psychological laboratory was established at last it was in behalf of a physiological point of view, and like many other theories imported from Germany we have still to estimate the physiological theory in its true estate. In the end it may seem as far from the truth as the idealism and criticism which we are in process of examining anew. If psychology is a sign of the times we may well remind ourselves that the end is not yet. For there are many rivals in the field. The implied psychology of the New Thought is essentially practical and decidedly unlike that mental science which holds that the inner life is wholly determined by the brain. For the devotee of mental healing the mind is what actual success seems to prove it to be in the endeavor of the soul to conquer circumstance. It is well to study the history of mental healing without regard to the psychology of the laboratories.

The new age began in part as a reaction against authority in favor of individualism and the right to test belief by personal experience. By acquiring the right to think for himself in religious matters, man also gained freedom to live according to his convictions. Inner experience came into its own as the means of testing even the most exclusive teachings of the Church. The seat of authority was found by some in human reason, by others in what the Quakers call the inward light. Thus inward guidance led the way to another and more spiritual phase of liberalism. The Emersonian idea of self-reliance is an expression of this faith in the light which shines for the individual within the sanctuary of the soul. After the mental- healing movement had been in process for half a century its devotees saw in Emerson a prophet of the ideas for which they had been laboring in their own way, each within the sphere of his experience. This emphasis on inner experience is a sign of our age, but it took us a long while to read the signs.

Now that we have passed into the social period we are able to appreciate the individualism of the nineteenth century. It was of course necessary for man to win the right to think for himself, to test matters for himself, and to become aware of his subjective life in contrast with the objective. Man had to plead for salvation as the individual’s privilege. He was eager to prove that the individual survived death, that a spirit could return and establish its identity. He also had to contend for the freedom of the individual in contrast with the tendency of evolutionism to regard man as a product of heredity and environment. Our whole modern view of success has grown up around a new conception of the individual. We have pleaded for man the individual in manifold ways since modern science made us acquainted with the theory of physical force, its laws, processes, and conditions. But in the twentieth century we have taken a long step beyond the individualism with which the modern liberal movement began.

The present is the dawning age of brotherhood. It marks an advance not only beyond the theoretical idealism which emphasized Thought as the only reality but beyond all types of theory in which stress is placed upon the subjective. We have come out into the open again after the age-long endeavor to acquaint man with the inner life. We penetrated the inner world to gain new insights, to acquire the psychological point of view, to discover the psychical, to learn about suggestion and the subconscious. We had to learn that all real development is from within outward according to law

Today we are engaged in applying our new discoveries. The history of the New Thought is for the most part the record of one of several contemporaneous movements in favor of the inner life and the individual. We can understand it now because our age has given us the contrast. To follow that history intelligently is to see in it an effort for knowledge and power which we now take as matter of course. Each of us has in a measure come to hold the present social point of view because those who went before earned for us the right to individual salvation, gave us the inner point of view.

It was the war more than any other event of our century which gave us the contrast through which we now understand the subjectivism of the nineteenth century. The war made us aware that we had traveled very far. It showed us the widespread social tendency of our age. It was the greatest objective social struggle the world has witnessed; for never was the autocrat. the mere individual so effectively organized as in this “last war of the kings.” Yet never was there such a social protest against every right which the mere individual takes unto himself in his effort to impose his ideas on the world.

As a result we now see plainly that all true peace is social. Our nation was brought out of its isolation into prominence as a world-power to secure this larger, lasting peace. As a result we realize that justice is social. We are all pondering over the nature of social justice. We are aware that this is the great issue, now that we have turned from the war as an external enterprise to interpret the warfare of the classes.

We are pleading for moral and spiritual considerations as eagerly as before. But we see that, strictly speaking, the moral and spiritual are neither subjective nor objective: they are social. Hence we look for every clue that points toward cooperation and brotherhood. We are passing beyond the old competitive spirit. The nations have been brought close by working for a common end. Never before has the world witnessed such a spirit of service.

This growing awareness of the intimacy of relationship of the individual with society has increased with us in line with the newer thought of God as immanent in the world, as the resident cause of all evolution. Our thought of God has become practical, concrete. This newer conception of God also belongs with the desire of the modern man to test everything for himself, to feel in his own life whatever man claims to have felt in the past that exalted him. Thus the practice of the presence of God follows as a natural consequence of the newer idea of man. The liberalism which set man free from the old theology left him free where he could turn to all the first-hand sources of religion for himself.

In a practical sense of the word we may say that the new age is witnessing a return to the original Christianity of the Gospels. The great work of religious liberalism in the nineteenth century consisted in freeing the world of theologies which we need never have believed. The war has brought us to the point where we can begin to appreciate what kind of social reform Christianity would have ushered in if it had been tried. The original teaching was social in the larger, truer sense. It called for brotherhood. It came to establish peace. It came that all men might have life and have it more abundantly. The spirit of the new age counsels us to return to the Bible as the Book of Life. It assures us anew that that which is spiritual must be spiritually discerned. It puts the emphasis on conduct, on the life. It came to minister to the whole individual. Only through social salvation can we begin to attain its fulness.

Granted the clues which our century affords us, we see clearly that the founders of Christian theology made a serious mistake when they divided the individual, assigning the problems of sin and salvation to the priest and neglecting the individual in the larger sense in which Jesus Christ ministered to him. Our age is giving the whole individual back to us. It is like a new discovery, this modern view of man as interiorly abounding in resources and outwardly social, a brother to all mankind. The last century witnessed the rediscovery of the inner life. The present is witnessing the rediscovery of man the social being. We are prepared at last to consider the question of health as at once individual and social. We had to understand man the social being before we could begin rightly to minister.

The original Christianity was a gospel of healing in which the problems of sin and disease, of the individual in his relation to society, were not separated. The values of this gospel as a religion of healing were lost to view for ages. Our age has disclosed them anew. The mental-healing movement came into being to make these values clear. Its pioneers had to contend for recognition amidst universal unfriendliness. They had to begin their work several generations ago that we might enjoy its benefits today. Some of the devotees had to stand for very radical views in order to attract attention. Thus Christian Science so-called had an office to perform in contrast with the materialism of the age. Extremes beget extremes.

Our part is to discern the neglected truths, as old as the hills, but covered over with doctrines and dogmas.

As a reaction against the materialism of the nineteenth century in favor of the original gospel of healing, we can hardly follow the history of the New Thought without reminding ourselves of the age as a whole against which it was a protest. But it would be easy to overestimate the influence of the environment in which the mental-healing movement appeared. A practical protest headed by people who work in a quiet way to relieve human ills is very different from an intellectual protest such as religious liberalism. A practical protest cannot be explained by reference to ideas alone. It is a protest in behalf of life. It is an appeal to conduct. It becomes known by its fruits long before it has a theory to give to the world. Its leaders educate themselves, not by going through the schools and assimilating the prevalent teachings, but by turning away to experiment for themselves.

When the new theories have at last been promulgated, we can look back and trace resemblances in history as a hole. But the new theories when propounded were probably far more out of accord with the generation in which they appeared than in harmony with it. The new views were for our own age, and that age had not come. We cannot in reality explain these views either by heredity or by reference to environment. The true explanation calls for a return to the idea that there is a purpose in creation. The new development began early enough so that it would be ready when needed.

In so far as the mental-healing movement began as a protest this protest or reaction was made in a particular way, very different from that of the reaction which gave us modern liberalism. Medical science was so far inferior to its present estate that it is difficult for us to put ourselves in sympathetic imagination back in Mr. Quimby’s time, in 1840, to see why he spoke of physicians as “blind guides leading the blind,” as “slave-drivers” compelling the sick to enter a bondage worse than that of slavery in the South. We need to divest the mind of very nearly every explanatory idea we now employ in order to account for the vigor of that reaction. The spirit of the new age was there potentially, but it was merely potential. Mr. Quimby was far from being aware of it. He was simply a pioneer investigator. Matters which we now understand by reference to psychology were still in such a crude state that people believed in a mysterious magnetic fluid by which a mesmeriser could put a subject into a curious state called “sleep.” Nothing that a mental healer would call promising had yet appeared. Disease was apparently an “entity” that attacked man from without. Whatever man may once have known about the influence of mind upon the body had been forgotten. Never had a pioneer so few paths to follow.

In retrospect, knowing the new age as we now do, we know of course that there were clues which might have been followed. There were books which Mr. Quimby could have read in which he might have learned the laws of the intimate relationships of mind and body. It seems natural for us to protest against medical materialism. We take it for granted that any one who is in search of health will try to find help in any direction that is promising. The gospel of healing in the original Christianity is so plain to some of us that we wonder how anyone could have missed it. But Mr. Quimby knew nothing about it. He had no psychological knowledge. The only defensible view concerning his relation to the new age which we can maintain is that the new light was shining in the inner world and anyone who was sufficiently free from his age to turn to it might be enlightened, even though he were uneducated as education is commonly understood in the world.

What we shall understand the new age to mean in this the spiritual sense of the word is this shining of a new light which cannot be accounted for by reference to anything external. To try to explain it by studying the tendencies of the age as matters of material or intellectual history would be to try to explain the higher by the lower. All real causes are spiritual. New leaders appear when they are needed. A new work

begins in the fitness of time according to the divine providence. To understand the causes we need a measure of the same enlightenment. The true verifications are those of experience. Unless you are willing to seek light and test the principles in question for yourself you may not expect to understand. The new age bids us go to the sources for ourselves. Those sources are discoverable through the inward light, by the aid of intuition, through appreciation of the spiritual meaning of the Scriptures. The life comes before the doctrine. It is the fruits which indicate the value. Hence Mr. Quimby said that the sick were his friends. Those who had been restored to health by spiritual means were convinced that there was a great truth in the new method of healing. All the early healers, writers and teachers were healed in the new way, and the ideas were put forth on the basis of experience.

In following the history of the New Thought we are therefore concerned with practical life. The intellectual movements of the new age do not explain its practical tendencies. We cannot account for the New Thought unless we learn the sources of the gospel of healing, without which the New Thought in its present forms would not have come into being.

Chapter 2 – QUIMBY THE PIONEER

PHINEAS PARKHURST QUIMBY was a pioneer in the truest sense of the word. He did not carry on his investigations in the mental world as the representative of any sect or school. He was not aware that treasures lay before him in the promised land which he was about to enter. Few men have owed so little to the age in which they lived. His ancestors were not in any way remarkable. His early life gave no indication of the public work to which his productive years were to be devoted. He is not to be accounted for by reference to his education in the schools or by reference to the books which he read. Consequently, there is no reason for inquiring into his life, ancestry, and environment, as we ordinarily study the life of a man who has been of service to the world. At the outset he was simply an explorer in a little known region, that is, a region little known in his day. He was like the hardy pioneer who makes his way through a primitive forest unaware of his destination, unacquainted with the difficulties along the way, and not burdened by the opinions of predecessors whose advice might have been misleading. When new lines of inquiry are to be developed for the good of mankind, God usually summons a man from the common walks of life, one who Is sufficiently open and responsive to follow where the wisdom within him leads.

There is a great advantage in leadership of this sort. For the pioneer becomes acquainted with all the obstacles and grows strong by overcoming them. Face to face with difficult situations, he must find a way to meet them. He is led to the first-hand sources of reality. He proves the principle which becomes to him a great truth because of his own immediate needs, and so he is able to appeal to tangible results by way of verification of his teachings. But those who merely follow, and that means the majority of mankind in every land and in all time, believe on authority and gradually lose touch with reality. Thus new pioneers, sages, or prophets are needed every now and then through the ages, to lead the way back to the original sources of life and truth. The moral would be, if we could read it, that we should all adopt the pioneer’s spirit and explore for ourselves, learning the great lesson taught by those who made their own way in new fields.

The spiritual pioneer in whose career we are at present interested lived a very simple early life. Born in a small New England town, he spent his entire life in New England, and his work was little known outside of Maine until after his death. He was born in Lebanon, New Hampshire, February 16, 1802. From there the family moved to Belfast, Maine, when he was about two years old. His death occurred in the latter place. January I6, 1866, at the close of twenty-five years in the practice of spiritual healing.

His father was a blacksmith, and his life and education were such as one might enjoy in the humblest of homes in a country town in New England. Mr. Quimby attended school as a boy for a brief period only, and he acquired knowledge of the elementary branches with such training as the district schools of the day afforded. The meagerness of his education is accounted for by the fact that there were few resources at hand, and his father was financially unable to give him other opportunities. If we conclude that he was in any degree an educated man, it will be because we deem education in the school of experience or in the inner life superior to that of the schools.

Mr. Quimby had an inquiring, inventive type of mind, and during his middle life he produced several inventions on which he obtained letters patent. He took great interest in scientific subjects but not in a way that led him to become a reader of scientific works. Nor was he ever a reader of books in general. His manuscripts contain remarkably few quotations or references, except that in his later years he frequently introduced passages from the New Testament in order to put his own interpretation upon them. He refers to but one philosopher by name, and he appears never to have heard of the names of the idealists, such as Berkeley and Emerson, whose philosophy might have aided him had he been acquainted with their works.

He felt no antagonism to the Church in his early years, but the churches seem to have had no direct influence upon him, and he did not take up the study of the New Testament until his investigations led him to a point where he believed he had a clue to its inner meaning. Although the title “doctor” has been applied to him, he was without medical or other therapeutic trainIng. In fact, he stood in avowed antagonism to the “old school” in the medical world. He was not a spiritist, despite the fact that the rise of spiritism in the United States was contemporaneous with his work, and despite the resemblance between some of his views and the teachings of spiritualists.

The reason for his lack of interest in books is found in the fact that he regarded most books as full of unproved assertions, whereas he was interested to test all matters for himself. He was fond of referring to most statements passing current in the world as knowledge in a somewhat skeptical way, since this boasted knowledge seemed to him mere “opinion,” in contrast with truth that could be established on a basis of verifiable evidence and sound reasoning. He did not raise objections as did people trained in the schools, through mere love of argument, but because by implication he already possessed intuitively those principles which were to guide him in his investigations. His awakening came, not through intellectual development in the usual sense of the word, but through the demands of practical experience.

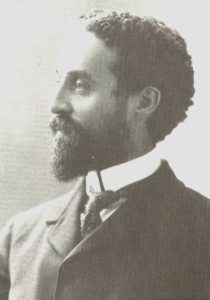

At the time Mr. Quimby began his investigations in the mental world he was described by a newspaper writer as “in size rather smaller than the medium of man, with a well-proportioned and well-balanced head, and with the power of concentration surpassing anything we have ever witnessed. His eyes are black and very piercing, with rather a pleasant expression; and he possesses the power of looking at one object, without even winking, for a great length of time.” His son, George A. Quimby, in the New England Magazine, March, 1988, adds to this description the fact that Mr. Quimby weighed about one hundred and twenty-five pounds; that he was quick-motioned and nervous, with a high, broad forehead, a rather prominent nose, and mouth indicating strength and firmness of will, “persistent in what he undertook, and not easily discouraged.”

Speaking of Quimby’s discoveries, Mr. Julius A. Dresser says, “If you think this seems to show that Quimby was a remarkable man, let me tell you that he was one of the most unassuming of men that ever lived; for no one could well be more so, or make less account of his achievements. Humility was a marked feature of his character (I knew him intimately). To this was united a benevolent and an unselfish nature, and a love of truth, with a remarkably keen perception. But the distinguishing feature of his mind was that he could not entertain an opinion, because it was not knowledge. His faculties were so practical and perceptive that the wisdom of mankind, which is largely made up of opinions, was of little value to him. Hence the charge that he was not an educated man is literally true. True knowledge to him was positive proof, as in a problem in mathematics. Therefore, he discarded books and sought phenomena, where his perceptive faculties made him master of the situation.* (*The True History of Mental Science.)

Another writer, speaking of the impression produced upon Mr. Quimby’s patients, says, “He seemed to know at once the attitude of mind of those who applied to him for help, and adapted himself to them accordingly. His years of study of the human mind, of sickness in all its forms, and of the prevailing religious beliefs, gave him the ability to see through the opinions, doubts, and fears of those who sought his aid, and put him in instant sympathy with their mental attitude. He seemed to know that I had come to him feeling that he was a last resort, and with but little faith in him or his mode of treatment. But, instead of telling me that I was not sick, he sat beside me, and explained to me what my sickness was, how I got into the condition, and the way I could be taken out of it through the right understanding. He seemed to see through the situation from the beginning, and explained the cause and effect so clearly that I could see a little of what he meant. . . .

“The most vivid remembrance I have . . . is his appearance as he came out of his private office ready for the next patient. That indescribable sense of conviction, of clear-sightedness, of energetic action—that something that made one feel that it would be useless to attempt to cover up or hide anything from him– -made an impression never to be forgotten. Even now in recalling it . . . I can feel the thrill of new life which came with his presence and his look. There was something about him that gave one a sense of perfect confidence and ease in his presence— a feeling that immediately banished all doubts and prejudices, and put one in sympathy with that quiet strength or power by which he wrought his cures.” * (*A. G. Dresser, The Philosophy of P. P. Quimby, p. 45.)

The attitude of mind which Mr. Quimby was in when he began to investigate is clearly indicated by the following from an article written in 1863 in which he describes what he calls his “conversion from disease to health, and the subsequent changes from belief in the medical faculty to entire disbelief in it,” and to the knowledge of the truth on which he based his theory of spiritual healing.

“Can a theory be found,” Mr. Quimby asks, “can a theory be found, capable of practice, which can separate truth from error? I undertake to say there is a method of reasoning which, being understood, can separate one from the other. Men never dispute about a fact that can be demonstrated by scientific reasoning. Controversies arise from some idea that has been turned into a false direction, leading to a false position. The basis of my reasoning is this point: that whatever is true to a person, if he cannot prove it, is not necessarily true to another. Therefore, because a person says a thing is no reason that he says true. The greatest evil that follows taking an opinion for a truth is disease. Let medical and religious opinions, which produce so vast an amount of misery, be tested by the rule I have laid down, and it will be seen how much they are founded in truth. For twenty years I have been investigating them, and I have failed to find one single principle of truth in either. This is not from any prejudice against the medical faculty; for, when I began to investigate the mind, I was entirely on that side. I was prejudiced in favor of the medical faculty; for I never employed any one outside of the regular faculty, nor took the least particle of quack medicine.

“Some thirty years ago I was very sick, and was considered fast wasting away with consumption. At that time I became so low that it was with difficulty I could walk about. I was all the while under the allopathic practice, and I had taken so much calomel that my system was said to be poisoned with it; and I had lost many of my teeth from the effect. My symptoms were those of any consumptive; and I had been told that my liver was affected and my kidneys diseased, and that my lungs were nearly consumed. I believed all this, from the fact that I had all the symptoms, and could not resist the opinions of the physician while having the [supposed] proof with me. In this state I was compelled to abandon my business; and, losing all hope, I gave up to die—not that I thought the medical faculty had no wisdom, but that my case was one that could not be cured.

“Having an acquaintance who cured himself by riding horseback, I thought I would try riding in a carriage, as I was too weak to ride horse-back. My horse was contrary; and, once, when about two miles from home, he stopped at the foot of a long hill, and would not start except as I went by his side. So I was obliged to run nearly the whole distance. Having reached the top of the hill I got into the carriage; and, as I was very much exhausted, I concluded to sit there the balance of the day, if the horse did not start. Like all sickly and nervous people, I could not remain easy in that place; and seeing a man plowing, I waited till he had plowed around a three acre lot, and got within sound of my voice, when I asked him to start my horse. He did so, and at the time I was so weak I could scarcely lift my whip. But excitement took possession of my senses, and I drove the horse, as fast as he could go, up hill and down, till I reached home; and, when I got into the stable, I felt as strong as ever I did.”

This experience was of course only the beginning. It led Mr. Quimby to doubt the diagnosis in his case.

It showed him what could be accomplished through a vigorous arousing out of a state of bondage and mere acceptance. He was not cured, but precisely what his malady was and how it would be overcome he did not know. It was his investigation of the phenomena of hypnotism, then called mesmerism, which gave him the direct clue.

The subject of mesmerism was introduced into the United States in 1836 by Charles Poyen, a Frenchman, and was taken up in New England by a Dr. Collyer, who gave a lecture with demonstrations in Belfast, Maine, in 1838. Mr. Quimby regarded the mesmeric sleep, or hypnosis as it would now be called, as an interesting phenomenon worthy of investigation, and without knowing what his interest would lead to he began to experiment, and in 1840 gave his first public demonstrations. Whenever opportunity offered, he had tried to put people into the mesmeric sleep. Sometimes he failed, but again he found a person whom he could influence.

“In the course of his trials with subjects,” says Mr. George A. Quimby in the account quoted from above, Mr. Quimby “met with a young man named Lucius Burkmar over whom he had the most wonderful influence; and it is not stating it too strongly to assert that with him he made some of the most astonishing exhibitions of mesmerism and clairvoyance that have been given in modern times.

“Mr. Quimby’s manner of operating with his subject was to sit opposite to him, holding both his hands in his, and looking him intently in the eye for a short time, when the subject would go into that state known as the mesmeric sleep which was more properly a peculiar condition of mind and body, in which the natural senses would or would not operate at the will of Mr. Quimby. When conducting his experiments, all communications on the part of Mr. Quimby with Lucius were mentally given, the subject replying as if spoken to aloud. . . .

“As the subject gained more prominence, thoughtful men began to investigate the matter; and Mr. Quimby was often called upon to have his subject examine the sick. We would put Lucius into the mesmeric state, who would then examine the patient, describe his disease, and prescribe remedies for its cure.

“After a time Mr. Quimby became convinced that, whenever the subject examined a patient, his diagnosis of the case would be identical with what either the patient or someone else present believed, instead of Lucius really looking into the patient and giving the true condition of the organs; in fact, that he was reading the opinion in the mind of someone rather than stating a truth acquired by himself.

“Becoming firmly satisfied that this was the case, and having seen how one mind could influence another, and how much there was that had always been considered as true, but was merely someone’s opinion, Mr. Quimby gave up his subject, Lucius, and began the developing of what is now known as mental healing, or curing disease through the mind.”

That this discovery concerning the influence of medical opinion and the influence of one mind on another was worth pursuing to the end is clear from Mr. Quimby’s account of the way he overcame his own illness. He was still in quest of health while experimenting with Lucius. His investigations showed him that there was a great discrepancy between the ordinary diagnosis and the actual state of a person suffering from disease, and it occurred to him that light could be thrown on his own malady. In fact, he had been led to believe by the astonishing results produced in cases where Lucius made an intuitive diagnosis that disease itself was, as he tells us, “a deranged state of mind,” the cause of which is to be found in someone’s unfortunate belief. “Disease,” he assures us, and its power over life, its curability, “are all embraced in our belief. Some believe in various remedies, and others believe that the spirits of the dead prescribe. I have no confidence in the virtue of either. I know that cures have been made in these ways. I do not deny them. But the principle on which they are done is the question to solve; for the disease can be cured, with or without medicine, on but one principle.”

When he had discovered what that principle was and how it could be employed, namely, by producing changes in the mind of the patient holding the belief in question and subject to medical opinion, with all that this dependence implies, he saw that it was no longer necessary to make use of his mesmeric subject, but that he could apply the principle directly himself. First, however, he had to prove the principle by recovering his own health.

“Now for my particular experience,” writes Mr. Quimby in the article quoted in The True History of Mental Science. “I had pains in the back, which, they said, were caused by my kidneys, which were partly consumed. I was also told that I had ulcers on my lungs. Under this belief, I was miserable enough to be of no account in the world. This was the state I was in when I commenced to mesmerize. 0n one occasion, when I had my subject asleep, he described the pains I felt in my back (I had never dared to ask him to examine me, for I felt sure that my kidneys were nearly gone), and he placed his hand on the spot where I felt the pain. He then told me that my kidneys were in a very bad state,– that one was half consumed, and a piece three inches long had separated from it, and was only connected by a slender thread. This was what I believed to be true, for it agreed with what the doctors had told me, and with what I had suffered; for I had not been free from pain for years. My common sense told me that no medicine would ever cure this trouble, and therefore I must suffer till death relieved me. But I asked him if there was any remedy. He replied, ‘Yes, I can put the piece on so it will grow, and you will get well.’ At this I was completely astonished, and knew not what to think. He immediately placed his hands upon me, and said he united the pieces so they would grow. The next day he said they had grown together, and from that day I never have experienced the least pain from them.

“Now what was the secret of the cure? I had not the least doubt but that I was as he described; and, if he had said, as I expected he would, that nothing could be done, I should have died in a year or so. But, when he said he could cure me in the way he proposed, I began to think; and I discovered that I had been deceived into a belief that made me sick. The absurdity of his remedies made me doubt the fact that my kidneys were diseased, for he said in two days that they were as well as ever. If he saw the first condition, he also saw the last; for in both cases he said he could see. I concluded in the first instance that he read my thoughts and when he said he could cure me he drew on his own mind; and his ideas were so absurd that the disease vanished by the absurdity of the cure. This was the first stumbling-block I found in the medical science. I soon ventured to let him examine me further, and in every case he could describe my feelings, but would vary about the amount of disease; and his explanation and remedies always convinced me that I had no such disease, and that my troubles were of my own make.

“At this time I frequently visited the sick with Lucius, by invitation of the attending physician; and the boy examined the patient, and told facts that would astonish everybody, and yet every one of them was believed. For instance, he told of a person affected as I had been only worse, that his lungs looked like a honey comb, and his liver was covered with ulcers. He then prescribed some simple herb tea, and the patient recovered; and the doctor believed the medicine cured him. But I believed the doctor made the disease; and his faith in the boy made a change in the mind, and the cure followed. Instead of gaining confidence in the doctors, I was forced to the conclusion that their science is false.

“Man is made up of truth and belief; and, if he is deceived into a belief that he has, or is liable to have a disease, the belief is catching, and the effect follows it. I have given the experience of my emancipation from this belief and from my confidence in the doctors, so that it may open the eyes of those who stand where I was. I have risen from this belief; and I return to warn my brethren, lest, when they are disturbed, they shall get into this place of torment prepared by the medical faculty. Having suffered myself, I cannot take advantage of my fellowmen by introducing a new mode of curing disease by prescribing medicine. My theory exposes the hypocrisy of those who undertake to cure in that way. They make ten diseases to one cure, thus bringing a surplus of misery into the world, and shutting out a healthy state of society. . . . When I cure, there is one disease the less. . . . My theory teaches man to manufacture health; and, when people go into this occupation, disease will diminish, and those who furnish disease and death will be few and scarce.”

Had Mr. Quimby been willing to take advantage of people, he might have continued to employ his subject in the diagnosing of disease, for it was evident that no one else understood the significance of his discovery that with a change of mind a cure would follow. If he had been content with his own restoration to health, he might have used his subject instead of exerting himself to develop his own mental powers. But, naturally honest and determined to get at the truth, Quimby dropped mesmerism once for all. And well he might, for his experiments had made him acquainted with himself. He saw that the human spirit possesses other powers than those of the senses, and can influence another mind directly, that is, without the aid of spoken language. He realized that he too possessed clairvoyant or intuitive powers, and that it was not necessary for the mind to be put into the mesmeric sleep in order to exercise these powers. His subject, Lucius, had done little more than to read the mind of a patient, discover what the person in question thought was his disease, and then prescribe some simple remedy in which the patient was led to believe. This was merely to make use of suggestion, as we now call it, and Quimby’s discovery had disclosed the mind’s suggestibility. Mr. Quimby wanted to go further. He was eager to know the full truth concerning disease and its cure by the one fundamental principle implied in all cases, whatever the appearances in favor of medicine. To have remained where his experiments with mesmerism brought him would have been to practice mental healing simply. Mr. Quimby’s impetus was spiritual, and he did not rest until he had acquired spiritual insight into the whole field of the inner life. His experiments with Lucius were merely introductory to his life work.

It is interesting to read what Mr. George Quimby says of his father’s discovery, for he was his father’s secretary for years and had opportunity to follow Quimby’s work with the sick in all its details, although he was not himself a healer.

Mr. Quimby informs us that his father spent years developing the method and theory of spiritual healing, fighting the battle alone, and laboring with great energy and steadiness of purpose. “To reduce his discovery to a science which could be taught for the benefit of suffering humanity was the all-absorbing idea of his life. To develop his ‘theory,’ or ‘the Truth,’ as he always termed it, so that others than himself could understand and practice it, was what he labored for. Had he been of a sordid and grasping nature, he might have acquired unlimited wealth; but for that he seemed to have no desire. . . .

“Each step was in opposition to all the established ideas of the day, and was ridiculed and combated by the whole medical faculty and the great mass of the people. In the sick and suffering he always found staunch friends, who loved him and believed in him, and stood by him; but they were but a handful compared with those on the other side.

“While engaged in his mesmeric experiments, Mr. Quimby became more and more convinced that disease was an error of the mind, and not a real thing; and in this he was misunderstood by others, and accused of attributing the sickness of the patient to the imagination, which was the reverse of the fact. ‘If a man feels a pain, he knows he feels it, and there is no imagination about it,’ he used to say. But the fact that the pain might be a state of the mind, while apparent in the body, he did believe. As one can suffer in a dream all that it is possible in a waking state, so Mr. Quimby averred that the same condition of mind might operate on the body in the form of disease, and still be no more of a reality than was the dream.”

In view of the fact that some one has tried to belittle Mr. Quimby as an “ignorant mesmerist” who never advanced beyond this crude mode of influencing people, it is significant to read this authoritative statement in his son’s account:

“As the truths of his discovery began to develop and grow in him, just in the same proportion did he begin to lose faith in the efficacy of mesmerism as a remedial agent in the cure of the sick; and after a few years he discarded it all together.

“Instead of putting the patient into a mesmeric sleep, Mr. Quimby would sit by him; and, after giving a detailed account of what his troubles were, he would simply converse with him, and explain the causes of his troubles, and thus change the mind of the patient, and disabuse it of its error and establish the truth in its place, which, if done, was the cure. . . .

“Mr. Quimby always denied emphatically that he used any mesmeric or mediumistic power. He was always in his normal condition when engaged with his patient. He never went into any trance, and was a strong disbeliever in spiritualism, as understood by that name. He claimed, and firmly held, that his only power consisted in his wisdom, and in his understanding the patient’s case and being able to explain away the error and establish the truth, or health, in its place. . . .

“In the year 1859 Mr. Quimby went to Portland, where he remained till the summer of 1865, treating the sick by his peculiar method. It was his custom to converse at length with many of his patients who became interested in his method of treatment, and try to unfold to them his ideas.

“Among his earlier patients in Portland were the Misses Ware, daughters of the late Judge Ashur Ware, of the United States Court; and they became much interested in ‘the Truth,’ as he called it.* But the ideas were so new, and his reasoning was so divergent from the popular conceptions that they found it difficult to follow him or remember all he said; and they suggested to him the propriety of putting into writing the body of his thoughts.

*See: The Spirit of the New Thought, “Can Disease be entirely Destroyed?” by Emma G. Ware, p.67

“From that time he began to write out his ideas, which practice he continued until his death, the articles now being in the possession of the writer of this sketch. The original copy he would give to the Misses Ware; and it would be read to him by them, and, if he suggested any alteration, it would be made, after which it would be copied either by the Misses Ware or the writer of this, and then reread to him, that he might see that all was just as he intended it. Not even the most trivial word or the construction of a sentence would be changed without consulting him. He was given to repetition; and it was with difficulty that he could be induced to have a repeated sentence or phrase stricken out, as he would say, ‘If that idea is a good one, and true, it will do no harm to have it in two or three times.’ ”

It was during the period of his more important practice in Portland that those patients visited him who were later to spread his ideas in the world. The first of these was Mr. Julius A. Dresser, who went to him as a patient when near the point of death in June, 1860, and who became so deeply interested in Mr. Quimby’s teachings that after regaining his health he devoted the larger part of his time to explaining the new ideas and methods of Mr. Quimby to patients. Among these patients was Miss Annetta G. Seabury, afterwards Mrs. Julius A. Dresser; and Mrs. Mary Baker Patterson, later Mrs. Eddy, author of Science and Health. In 1863, Rev. W. F. Evans visited Mr. Quimby as a patient and became at once so ardent a follower that he devoted the remainder of his life to promulgating the spiritual philosophy implied in the method and ideas which he gained from Quimby.

It was Mr. Quimby’s intention to retire from his practice with the sick and write a book setting forth his teachings in permanent form. Had he done so, there would have been no controversy over the origin of mental healing in our day, and the later writers would not have acquired the habit of setting forth his views as if they had been original enough to acquire them out of the air by “revelation.” But Mr. Dresser always maintained that there was a wisdom in the delay, since the public was then unprepared for them. Mr. Evans, who became the first author to develop these ideas, was perhaps better fitted for his work than was Mr. Quimby, since he was well read and able to put forth those ideas which were best calculated to win the public at the time he wrote. Meanwhile, the manuscript books into which Mr. Quimby’s articles were copied have been preserved and some of us have had access to them in connection with our work of giving the new ideas to the world.

Mr. George Quimby concludes the account of his father’s life with a brief reference to Mr. Quimby’s view of life as a whole: “Mr. Quimby, although not belonging to any church or sect, had a deeply religious nature, holding firmly to God as the first cause, and fully believing in immortality and progression after death, though entertaining entirely original conceptions of what death is. He believed that Jesus’s mission was to the sick, and that he performed his cures in a scientific manner, and perfectly understood how he did them. Mr. Quimby was a great reader of the Bible, but put a construction upon it thoroughly in harmony with his train of thought.

“Mr. Quimby’s idea of happiness was to benefit mankind, especially the sick and suffering; and to that end he labored and gave his life and strength. His patients not only found in him a doctor, but a sympathizing friend; and he took the same interest in treating a charity patient that he did a wealthy one. Until the writer went with him as secretary, he kept no accounts and made no charges. He left the keeping of books entirely with his patients; and, although he pretended to have a regular price for visits and attendance, he took as settlement whatever the patient chose to pay him. . . .

“An hour before he breathed his last he said to the writer: ‘I am more than ever convinced of the truth of my theory. I am perfectly willing for the change myself, but I know you will all feel badly; but I know that I shall be right here with you, just the same as I have always been. I do not dread the change any more than if I were going on a trip to Philadelphia.’ His death occurred January 18, 1866, at his residence in Belfast, at the age of sixty-four years. . . .”

Chapter 3 – QUIMBY’S METHOD OF HEALING

IT was a long step from dependence on the medical practice of the day to Mr. Quimby’s experiments with his subject, Lucius. It was a much longer step, involving a more courageous departure from accepted beliefs, when he gave up his subject and developed a mode of treatment not at that time practiced anywhere else in the world. The first change was from one theory of mental life to another, and the change did not necessarily imply a different view of the natural world. But the second was radical. It implied a spiritual philosophy of life as a whole. The emphasis was shifted from human beliefs in relation to bodily processes to divine causality and its meaning in the progress of the human soul. Mr. Quimby’s discovery concerning the influence of belief in the cause and cure of disease was incidental to his profounder discovery that man is a spiritual being, living an essentially spiritual life in the higher world above the flesh, the eternal spiritual world of our relationship with God.

The progress which Mr. Quimby thus made was natural and logical. His experiments first made him acquainted with the clairvoyant or intuitive powers of his subject, Lucius, then showed him that he too possessed such powers and so need not depend on Lucius. His reasoning was that these higher powers in the human spirit imply the existence of a guiding principle or wisdom common to us all, that this principle is God in us; hence that the soul is in immediate relation with the divine mind. Furthermore, he had concluded that, whatever the explanation offered, all healing takes place according to one principle, and this too he attributed to the divine in man. His experiments had taught him that one mind can influence another directly, the one being receptive, the other affirmative. It was but one step more to adopt the principle that as thought may influence another’s mind directly spiritual power is capable of such influence too. Hence Mr. Quimby advanced from the discovery that thoughts and mental atmospheres affect another’s mind according to the belief or expectation to the conclusion that one spirit may operate directly on another spirit, and that the basis of this spiritual activity is the divine in us. Although naturally active, affirmative in type, with exceptional powers of concentration, Mr. Quimby was as we have seen above also humble, not inclined to take credit to himself. It was natural, therefore, that he should reach the highest conclusion of all, namely, that the efficiency was divine, that it was through the divine wisdom that he achieved his cures.

The acceptance of these principles and conclusions implied a different philosophy of life because, in the first place, it became clear that all reality fundamentally speaking is spiritual. Mr. Quimby did not undertake to develop his theory into a philosophy of the universe as a whole. That was not his province. Nor did he have the training or the acquaintance with idealism. The references to the outer world which

he makes in his manuscripts were purely practical in nature, to the effect that life for each of us is essentially what we make it by our belief, our attitude or way of taking it. This attitude was, for most people, so he saw clearly, largely the effect of opinions taken for truth. But he also saw that there was a way of taking life which implied the supremacy of the spiritual over the material. For him all causes were in reality spiritual. The world springs from spiritual sources. Experience is for the benefit of spiritual beings. We might then acquire a complete spiritual view. This would disclose the truth in contrast with mere opinion, the truth which is the same for all. It would imply a spiritual science. And this science was involved in the method by which Mr. Quimby wrought his cures.

The instructive consideration for those of us who are concerned to follow the development of this philosophy and test its principles for ourselves lies in the fact that Mr. Quimby found the guiding principle in his own inner experience, and proved it through the recovery of his health and the healing of others before he found any evidences that what he called “the truth” or “theory” had ever been held before. Fortunately, his mind was not encumbered by doctrines which had first to be outgrown, save that he had shared the conventional beliefs of his day in medical practice and was at least a believer in a general way in the Bible. His real study of the Bible began with the conclusion that the way which life had led him was the way described in the New Testament, hence that he had rediscovered the method of healing by which Jesus wrought, not his “miracles,” but his highly intelligible works of healing. His work with the sick seemed to him to imply a spiritual science, a “science of life and happiness,” as he called it. This science he found implicit in the teachings of Christ. The Bible thus became doubly true for him, because of his former belief in God, now transfigured in the light of his discoveries; and because his insight into the nature and meaning of life had made plain the way to the spiritual interpretation of the Scriptures.

His manuscripts are for the most part devoted to a study of his experiences with the sick in such a way as to show that the truths they implied were the truths which Jesus came to reveal.

Just as his guidance had led him to attribute his cures, which were indeed remarkable, to the divine efficiency, not to any power which he, the man Quimby, possessed; so now he looked to the Bible as containing a higher than human wisdom, a wisdom which he called “the Christ” in contrast with the man Jesus who came to teach this science of the Christ. Had Mr. Quimby been understood by the writer who later did more than anyone to popularize the less profound principles for which he stood, the history of the mental-healing movement might have been very different. For what Mr. Quimby intended was that all should come to recognize the divine wisdom in themselves, that they should take no credit to themselves, should not exalt the finite self; but should acquire and teach the spiritual principles which Jesus gave to the world as a science, calling attention to that science, not to themselves.

According to Mr. Quimby’s version of this Christian science, as he calls it in two of his articles, although his usual term is “the science of life and happiness,” the emphasis is put upon the truth which sets the soul free. For his practice with the sick had taught him that when a patient understood the real causes of his trouble the disease could be banished. The “explanation is the cure,” he repeatedly said. This explanation involved the discovery of the inner or spiritual point of view. The emphasis being put upon the truth, Mr. Quimby did not make use of “denials,” as the affirmations were later called by those who grasped this theory in part only. When the truth is seen, it is not necessary to deny its opposite. The error or “false belief” that led to the trouble was negative or destructive. The truth through which the cure was wrought was positive or constructive. What Mr. Quimby endeavored to do was to build up a different attitude toward life on the basis of principles which all could understand.

Mr. Quimby’s departure from the point of view of his experiments therefore involved a radical change in attitude towards a patient. The mesmeriser or hypnotist merely tries to influence or control another’s mind, as Quimby directed Lucius. But the spiritual healer regards himself as an organ of the divine life, a means only, not a controlling agent. He does not try to influence. He makes no attempt to control. He has no desire to control or manage. He regards himself as a lamp-bearer disclosing the way out of the dark places of the soul into the light of the divine wisdom. There can be no freedom and no cure unless the patient sees for himself. Thus Mr. Quimby was healer and teacher at the same time. Unless we understand this two-fold office which he fulfilled, we are likely to misinterpret statements, such as the proposition that “disease is an error the only remedy for which is truth,” and we are in danger of dismissing many of his views as absurd.

To understand what Mr. Quimby meant is to see that he regarded every man in the light of the divine guidance. That is, there is divine wisdom for each of us, resident within us, accessible through intuition. Mr. Quimby was the friend of those who needed to be brought into relation with the divine within them. He sought the guidance for the individual in question, according to need, for the occasion. Naturally then there could be no mere formula or arrangement of words, no magic affirmation by which to dismiss a disease as with a gesture of command. There was no reason to deny either what the patient thought was his disease or the physical symptoms, to ignore the body or make light of the natural world. What was needed was a new point of view of all these things. The misinterpretation of symptoms would disappear with the acceptance of the true view. The bodily effect would be understood when the cause should become plain. The flesh would assume its proper place in the light of the new spiritual vision.

Mr. Quimby aimed at nothing short of a religious or spiritual conversion such that the whole of life should appear under a different aspect. This wonderful work he wrought for his more responsive followers. It is not surprising that they became his friends and found occupation for a lifetime in the development of his teachings.

There was one more discovery which we need to bear in mind in order to have Mr. Quimby’s method completely before us. His practice with the sick in the early years while he was acquiring his method taught him that there is much more in the human mind than we are ordinarily or even at any time conscious of. Not by any consent on our own part have we become the recipients of the beliefs, notions, and ideas which give us our erroneous views of life. We have taken them on from our mental environment.

Our minds are fertile places in which beliefs germinate. The mind in this deeper, hidden sense, is indeed very much like the soil. It consists of spiritual substance, “spiritual matter” was Quimby’s term at first.

Its products directly influence us and our bodies without the intervention of the will. It is indeed unconscious or subconscious. But this hidden mind is accessible to the spiritual healer. Its contents can be discerned. The hidden and disturbing influences can be brought to light. Changes wrought within it will become manifest in the body. It is in fact an intermediary between mind and body, an intermingling substance.

In contrast with the beliefs discoverable in this hidden mind, Mr. Quimby in the constructive part of his treatment addressed himself to the “real man,” the spirit, who needed to be summoned into power. He held that there is a part of the soul that is not sick, that is potentially or ideally one with God in image and likeness. For God did not create man to be ill. He created him for health and freedom. Disease is the invention of man through misinterpretation of sensation, through judgments based on appearances, on symptoms, effects, externals. Health is ours by divine birthright, hence by implication in our very being in that “secret place” of the soul, that part of us that can never be ill. This element of our selfhood can be summoned into activity. We can become aware of it and begin to live by it. We can throw off our bondages. We can learn to live as God would have us live.

The silent spiritual treatment which was Mr. Quimby’s chief discovery, his greatest gift to the world, consisted in a process of inner realization calculated to awaken this inner spiritual nature into exercise. The intuitive diagnosis with which the treatment began led the way to the main point, the centre of need

in the patient. It disclosed the real as opposed to the apparent condition. It yielded the divine guidance for the occasion, according to the need. The spiritual realization then grew out of the intuitive discovery of the patient’s inner state. It was made effective by Mr. Quimby’s great power of concentration quickened by his consciousness of the divine wisdom, his practical way of realizing the presence of God. The treatment was spiritual rather than mental since the thought or idea was secondary to the power, the human agent or organ secondary to the divine wisdom. Mr. Quimby had no way of his own to impose on another’s mind. Hence his spirit was open to “the wisdom of the occasion.”

In setting forth his method of treatment, Mr. Quimby always drew a distinction between the lower mind which he called “spiritual matter” (or substance), and the mind we might come into possession of by learning our true nature as spiritual beings. Thus he says in one of his articles, “My theory is founded on the fact that mind is matter; and, if you will admit this for the sake of listening to my ideas, I will give you my theory . . . All knowledge that is of man is based on opinions. This I call this world of spiritual matter. It embraces all that comes within the so-called senses. Man’s happiness and misery are in his belief; but the wisdom of science is of God, and not of man. Now to separate these two kingdoms is what I am trying to do: and, if I succeed in this, I shall accomplish what never has been done. . . . I should never undertake the task of explaining what all the wise men have failed to do but for the want of some better proof to explain the phenomena that come under my own observation. . . . The remedies have never destroyed the cause, nor can the cause be destroyed by man’s reason. . . .

“The world of opinions is the old world: that of science is the new; and a separation must take place, and a battle must be fought between them. Now, the science of life and happiness is the one that has met with the most opposition, from the fact that it is death to all opposers. It never compromises with its enemies, nor has it any dealings with them. . . . Its habitation is in the hearts of men. It cannot be seen by the natural man, for he is of matter; and the scientific man is not matter. All he has is his [spiritual] senses. There is his residence for the time. . . . It is almost impossible to tell one character from another, as both communicate through the same organs. As the scientific man has to prove his wisdom through the same matter that the natural man uses, he is often misrepresented. . . .This was where Christ found so much trouble in his days, for the people could not tell who was speaking.”

Mr. Quimby described human life as a warfare between the spiritual power in man and the opinions which relate and bind him to the natural world. When he says, “My foundation is animal matter or life,” he refers to the lower mind with its opinions. “This,” he says, “set in action by Wisdom, produces thought. Thoughts, like grains of sand, are held together by their own sympathy, wisdom, or attraction.” The natural man is composed of these groupings of ideas. “As thought is always changing, so man is always throwing off particles of thought and receiving others. Thus man is a progressive idea; yet he is the same man, although he is changing all the time for better or worse.” That is, he changes in the direction of the world with its opinions or towards God in His wisdom.

“Disease is the invention of man, and has no identity in Wisdom,” that is, no place or purpose in the divine providence. It can be overcome because the mental life underlying it is of this lower mind which can be changed by the Wisdom which “decomposes the thoughts, changes the combinations, and produces an idea clear from the error that makes a person unhappy or diseased.” “Ideas have life. A belief has life . . . for it can be changed.” Man is unwittingly a “sufferer from his own belief. . . . Our belief cannot alter a scientific truth, but it may alter our feelings for happiness or misery. Disease is the misery of our belief, happiness is the health of our wisdom, so that man’s happiness or misery depends on himself.” The difficulty does not lie with sensation, for “sensation contains no intelligence, but is a mere disturbance which . . . is ready to receive the error, that is, respond to an erroneous interpretation. . . . Ever since man was created, there has been an element called error which has been busy inventing answers for every sensation.”

Mr. George Quimby, in endeavoring to make clear this point of view, uses the following illustration: “Suppose a person should read an account of a railroad accident, and see, in the list of killed, a son. The shock on the mind would cause a deep feeling of sorrow on the part of the parent, and possibly a severe sickness, not only mental but physical. Now, what is the condition of the patient? Does he imagine his trouble? Is his body not affected, his pulse quick; and has he not all the symptoms of a sick person, and is he not really sick? Suppose you can go to him and say to him that you were on the train, and saw his son alive and well after the accident, and prove to him that the report of his death was a mistake. What follows? Why, the patient’s mind undergoes a change immediately; and he is no longer sick. It was on this principle that Mr. Quimby treated the sick. He claimed that ‘mind was spiritual matter,’ and could be changed; that we were made up of truth and error; that disease was an error, or belief, and that the Truth was the cure. And upon these premises he based all his reasoning, and laid the foundation of what he asserted to be the ‘science of curing the sick.’ ” * (*The Philosophy of P. P. Quimby, p. 18.)

In one of his articles, written in 1861, Mr. Quimby thus describes his method of cure: “A patient comes to see Dr. Quimby. He renders himself absent to everything but the impression of the person’s feelings. These are quickly daguerreotyped on him. They contain no intelligence, but shadow forth a reflection of themselves which he looks at. This [mental picture] contains the disease as it appears to the patient. Being confident that it is the shadow of a false idea, he is not afraid of it. Then his feelings in regard to health and strength, are daguerreotyped on the receptive plate of the patient. . . . The patient sees . . . the disease in a new light, gains confidence. This change is daguerreotyped on the doctor again . . . and he sees the change and continues . . . the shadow changes and grows dim, and finally disappears, the light takes its place, and there is nothing left of the disease.”

A writer in the Jeffersonian of Bangor, Maine, in 1857, thus expounds Quimby’s view: “A gentleman of Belfast, Maine, Dr. Phineas P. Quimby, who was remarkably successful as an experimenter in mesmerism some sixteen years ago, and has continued his investigations in psychology, has discovered, and in his daily practice carries out, a new principle in the treatment of diseases. . . . His theory is that the mind gives immediate form to the animal spirits, and that the animal spirit gives form to the body, as soon as the less plastic elements of the body are able to assume that form. Therefore, his first course in the treatment of a patient is to sit down beside him, and put himself en rapport with him, which he does without producing the mesmeric sleep.

“He says that in every disease the animal spirit, or spiritual form, is somewhat disconnected from the body, and that, when he comes en rapport with a patient, he sees that spirit form standing beside the body, that it imparts to him all its grief and the cause of it, which may have been mental trouble or shock to the body, as over-fatigue, excessive cold or heat. This of course impresses the mind with anxiety, and the mind reacting upon the body produces disease. . . .

“Dr. Quimby says that there is no danger from disease when the mind is armed against it. That he will treat a person who has the most malignant disorder without danger to himself, though his sympathy with the patient is so strong that he feels in his own person every symptom of the disease; but he dissipates from his mind the idea of it, and induces in its place an idea of health.

“He says the mind . . . is what it thinks it is, and that, if it contends against the thought of disease, and creates for itself an ideal form of health, that form impresses itself upon the animal spirit, and through that upon the body, that his understanding is a positive power, and aids the spirit, which is not strong enough in itself to contend against the idea of diseases.” * (*The Philosophy of P. P. Quimby, p. 22.)

For the term “animal spirit” as used by this writer one should substitute the unconscious, the spiritual substance or “spiritual matter” of Mr. Quimby’s later teaching, together with his teaching that the individual gives off a mental atmosphere as a rose gives off an odor by the discernment of which the healer can detect the patient’s interior state; otherwise the above account gives an intelligible idea of the psychological aspect of the treatment. Mr. Quimby held that there is a spiritual body between the natural body and the human spirit. In this he agreed with seers of an earlier time, and pointed the way to the idea of the intimate correspondence between the spirit and the body. He did not teach that the spirit-forms of the departed occupy our bodies, or that disease in any of its forms is due to obsession.

Another interested observer wrote as follows in an article in the Portland Advertiser, February, 1860: “In every age there have appeared individuals possessing the power of healing the sick and fore-telling events. Their theory or explanation veils this power in superstition and ignorance, so that the world is not enlightened in regard to where it comes from or how it operates. We only know the effects. Spiritualists, mesmerists, and clairvoyants, making due allowance for imposition, in later times have proved that this power is still in existence.

“Like this in the vague impression of its character, but infinitely beyond any demonstrations of the same intelligence and skill, is the practice of a physician who has been among us . . . and to whose treatment some helpless invalids owe their recovered health. I refer to Dr. P. P. Quimby. With no reputation except for honesty, which he carries in his face, he has established himself in our city, and his success merits public attention. Regarded by many as a harmless humbug, by others as belonging to the genus mystery, he stands among his patients as a reformer, originating an entirely new theory in regard to disease, and practicing it with a skill and ease which only come from knowledge and experience. His success in reaching all kinds of diseases, from chronic cases of years’ standing to acute diseases, shows that he must be practicing upon a principle different from what has ever been taught.

“His position as an irregular practitioner has confined him principally to the patronage of the credulous and the desperate; and the most of his cases have been those which have not yielded to ordinary treatment, Those only who have been fortunate enough to receive benefit from him can have any appreciation of the interest which the originality of his ideas excites, and of the benefit, when understood, which they will be to society.

“To attempt to describe his mode of treatment to the well would be like offering money to an already wealthy man; while the sick person who is like one cast into prison for an unjust debt, can tell the force of his system. With a sympathy which the sick alone call forth, and a knowledge which he proves alone to them, he leads an invalid along the path to health. His power over disease arises from his subtle knowledge of mind and its relation to the natural world, to which his attention was turned some twenty years ago by mesmerism.