CONTENTS

PREFACE

CHAPTER I. THE SEARCH FOR UNITY

CHAPTER II. RECENT TENDENCIES

CHAPTER III. A NEW STUDY OF RELIGION

CHAPTER IV. PRIMITIVE BELIEFS

CHAPTER V. THE LARGER FAITH

CHAPTER VI. LINES OF APPROACH

CHAPTER VII. THE SPIRITUAL VISION

CHAPTER VIII. THE PRACTICAL IDEALISM OF PLATO

CHAPTER IX. PLOTINUS AND SPINOZA

CHAPTER X. THE OPTIMISM OF LEIBNIZ

CHAPTER XI. THE METHOD OF EMERSON

CHAPTER XII. PHILOSOPHY

CHAPTER XIII. BERKELEY’S IDEALISM

CHAPTER XIV. THE ETERNAL ORDER

CHAPTER XV. EVOLUTION

CHAPTER XVI. LOWER AND HIGHER

CHAPTER XVII. CHRISTIANITY

CHAPTER XVIII. THE IDEA OF GOD

CHAPTER XIX. CONSTRUCTIVE IDEALISM

PREFACE

Probably all thoughtful people would agree that the relation of man to the universe is the profoundest theme that can engage the human mind, but not all would agree in regard to the method to be employed. The present volume aims to meet various practical and philosophical demands without insisting upon any one method except the spontaneous development of thought. Hence these essays, written at different times and not in the order here printed, have not been reduced to a consecutively developed whole. Chapter V., originally a lecture entitled “The Divine Order,” gave the clue to the unifying thought; Chapter XI. exemplifies the prevailing method; and the discussion of Plato’s idealism contains the supplementary principle. Chapters XII.—XVI. are largely concerned with objections to the general doctrine; the exposition of Christianity is a further development of the interpretation published a few years ago in The Christ Ideal; while the last chapter outlines the system implied in the various discussions, as well as in the ten volumes of essays which preceded the present more mature volume. The fundamental thought of the book is so dependent on the empirical value of each chapter that it is impossible to suggest it in advance. Empirical from first to last, the book will profit the reader in so far as the leading ideas are tested not only by reference to accepted religious and philosophical standards, but in relation to the realities and ideals of individual experience.

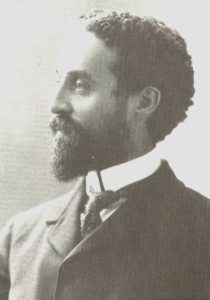

H. W. D.

Cambridge, Mass.,

July, 1903.

Chapter I. The Search for Unity

Plato once defined philosophy as “a meditation on death” At first thought, this characterisation seems absurd, and more than one thinker of note has protested against it. But in a sense it is profoundly true. Ordinarily, man has little interest in the consideration of life as a whole. The easy routine of animal existence, the fascination of business and social life is usually more inviting. Prosperity is not the parent of speculation. But when an unusual event occurs,—a volcanic explosion, a terrible earthquake, or the loss of a passenger steamer at sea with all on board,—thousands of troubled people seek an explanation of the catastrophe. Why did God permit it? is the customary query. How happens it that we are spared? Is our turn likely to come in such startling fashion? Superstition vies with theology and metaphysics in the endeavour to answer. Nothing more surely reveals the degree of superstition remaining than these speculative attempts to account for a great calamity.

Private misfortune as readily drives man into the realm of speculation. Many a man has become an atheist when, suddenly and cruelly, as it seemed to him, he was bereft of wife or child. Not until the hand of death strikes its heartless blow do men and women begin eagerly to inquire if there be another world. Calamity usually brings either despair or faith, for the same hardship which unmakes the belief of one may be the occasion for the fruition of another’s faith. Not until we are forced are we inclined to think profoundly. Scepticism is as likely to be the first result as conviction. But at any rate the mind is in activity, and in movement there is life. Something to account for which demands his entire wit—that is the boon of the philosopher. Religion, too, grows by dint of doubt and despair, and close upon the profoundest sorrow the most sustaining sense of love may come.

The history of primitive man undoubtedly followed the same course. As long as the chase was successful, and there was an abundance to eat, our prehistoric brothers probably did not trouble about the nature of things. But when floods and famines came, wars and pestilences, the whole face of things was changed. If a thunderstorm broke into the harmony of the savage’s life, it was natural to think that some being in the sky was angry. The myths that have come down to us show that human imagination was as fertile thousands of years ago as now in proposing hypotheses to account for calamities. But when our ancient ancestors stood in the presence of death—what could have been more provocative of philosophic thought? Then meditation began in earnest, and did not stop short of belief in a certain degree of unity as attributable to the nature of things, a unity which at least sufficed until some fresh catastrophe broke startlingly in upon man’s philosophic repose.

The first explanations were, of course, crude and mythological, though perhaps no more fantastic than some of the theories of the divine wrath proposed in modern times. But these myths all bore the same stamp. Something had broken into the usual round of things, and that something was misunderstood. Man is a lover of success, hence an explanation must be sought. If the calamity was apparently due to an angry god, that god must be propitiated. If some one had sinned, some one must suffer. For practically and theoretically man is a lover of unity,—both his peace of mind and his business are dependent on it. But his reaction was undoubtedly practical and poetic long before it was what we should call philosophical.

For primitive man evidently believed in a chaos of unities, rather than in a well-knit whole. Different deities were supposed to preside over different functions in nature and in human life. Each time one of the deities got out of humour he must be individually propitiated. There was peace only in those happy moments when no god chanced to be angry. In course of time each function in life came to have its deity; and if man had philosophised he would have been compelled to confess that the ultimate world of things was such that a polytheistic host somehow existed contemporaneously, despite their warrings. The deities grew in numbers, instead of decreasing. It is with genuine sympathy that we consider the mass of obligations by which people were fettered in early civilised times. It is with true insight into the perplexities of the case that Shakespeare makes Cassius exclaim, “Now in the name of all the gods at once!” From the tending of the sacred fire in the precincts of home to the public festivals, the preparation for war, and the settling of public and private difficulties, the Greeks and the Romans were everywhere beholden to these mythological adaptations, the sum of which was supposed to make life desirable and successful.

In India, mythology gradually melted into spiritual pantheism, so that escape from the perplexities of a thousand unities was found in one great whole, without parts, where perfect bliss was attained. The entire process of adjustment and readjustment, as this change went on, is portrayed in the Vedas and Upanishads. Absolute unity once attained, every possible problem was settled by reference to that. In other lands, also, the assumption of absolute unity has seemed the best way out of the confusion; and mysticism in various forms has always been an inviting resource. But in the Western world the tendency has been largely toward individuality of theory and adaptation to the world, so that for the majority unity in the genuine sense of the word is still an ideal.

The reactions of primitive man tended to take an animistic form, so Tylor and the other anthropologists tell us. That is, man interpreted the phenomena of nature by reading his own feelings into them. Man felt the pulsations of life within, the beating of his heart and the other physiological activities, and naturally regarded the signs of life around him as indications of the existence of similar beings behind or within everything that moved. The flowing river was a thing of life, the cloud was animated,—even trees and stones were regarded as alive. Hence it was natural to attribute all unusual phenomena to souls or deities, active in the storm, in the flood, or the rumblings of the earthquake. All the world was alive for primitive man. The idea of matter as dead or inert is a recent theory. Death itself was supposed to be due to a living being of some sort: for example, when a man was drowned in some “hostile” river. Hence all man’s dealings with death and the departed were based on the thought of life. It was a low form of belief, to be sure. Sometimes the soul was actually identified with the pulse, the breath, or the blood. But nevertheless it was belief in life, which was everywhere held to be the cause of movement,—so the recorded beliefs and myths indicate, and so linguistic remains tell us; hence the personifications, the tales told about the deities who were supposed to be active in nature. The natural function was practically identified with a god in many of these early myths. Thus the Hindoo god Agni was literally the fire which men could kindle, the fire which “flared up,” and the same that flashed in the sky. But little by little the supposed deity was disengaged from his natural basis and addressed in the sacred hymns as a person. Greek mythology in time became so personal that dramatic incidents entirely took the place of the old-time nature- activities. But even here man still read his own life into the activities which he poetically described.

We may safely say, then, that the first general conception of unity which science enables us to reconstruct is the idea that all nature is animated by beings resembling man. The first great thought was the conception of life,—a wonderfully poetic idea it seems at this distance. For imagine the emotions of man in the presence of a waterfall, whose leapings were regarded as the movements of a living being! In another sense, this animism was a terrible idea, since man seemed to be surrounded by a peopled world where there were many unfriendly spirits, so that he had to be constantly propitiating, offering up the firstlings of the flock, if not making sacrifices of human beings. Those were days of superstition such that it is practically beyond our powers of imagination to picture man’s emotional reactions. Anthropologists warn us that we must first endeavour to put ourselves in primitive man’s place as an emotional being, before we venture to conceive of his beliefs. For primitive man was doubtless a creature of great emotions of awe and fear, cosmic feelings, such as we never know in our highly intellectual age. These emotional reactions probably came long before the period of articulate belief,—poetry far antedated science. When definite beliefs at length began to appear they were tardy expressions of what man had long felt, and hence they came out of his most intimately personal life.

That animism, or the interpretation of all motion in terms of life similar to man’s life, was universal we have evidence in the great collections of myths which scientific men have made in recent years. There is remarkable similarity in corresponding myths gathered from all over the world, whether the myths are thousands of years old or believed by men who are still in the stage of development of the great savage peoples of the past. Thus myths gathered in Africa and Australia may throw light on the myths of ancient Greece and Rome. Students of Greek philosophy are familiar with the survivals of some of these ancient beliefs which are found even as late as the writings of Plato and Aristotle. The idea that the soul, or at any rate one of man’s psychic functions or souls, was the source of movement in the body persisted to the end in Greek psychology. In fact, animism was the accepted theory of movement until the Greek philosophers advanced a better notion. There was no break between Greek mythology and Greek science. The cosmogonic poetry of Hesiod took the place of earlier accounts of the origin of things. Then the cosmological theories of the Ionians were brought forward as substitutes. But the more scientific principle proposed by Thales, namely, “water,” was still a kind of divine, poetic somewhat; nature was still said to be “full of gods”

Thus, if we would reconstruct the various conceptions of unity which men have entertained we must start with animism, with mythology in its various forms, regarded as taking the place of what we now differentiate as science and religion. That is, these ancient myths were sometimes beliefs in magical powers which man believed he could use to his advantage, and again they were religious beliefs expressive of his awe in the presence of nature, or his belief in immortality and the land of the blessed dead. What we call science disengaged itself but slowly and very late. To the degree that science flourished, mythology disappeared. Its appearance in ancient Greece marked one of those stages noted above when the old unity was broken into, when man was no longer satisfied to regard the universe as the field of activity of multitudes of gods. More strictly speaking, it was not till science appeared that man could in any real sense regard the world as one. When man began to think systematically, polytheism no longer met his demands; hence his centre of interest was shifted.

We are reminded by the above reference to India, however, that for many millions of people a religious way of regarding things as a unitary whole has sufficed, so that the need of what we in the West call science has not been felt. Two unities broke free from the original polytheism which once held sway. The history of thought in India is in many ways decidedly unlike that of the West. According to our scientific men, there is no unity at all where there is no systematic principle. But the great movement of thought which began in crude polytheism and culminated in Hindoo pantheism, to the disparagement of all methods of knowing except spiritual contemplation, is one of the most profoundly suggestive chapters in human life. To condemn the result as unsound, without long and careful inquiry, would be as great a mistake as to read our modern ideas into the myths of savage times. If we would do justice to man’s unitary beliefs, we must imaginatively put ourselves in the place not only of those who regard the world as the product of an extramundane creator, but of those who deem the world itself a great living being; or of those, on the other hand, who declare that there is but one great Self, “Brahman”—”one, without a second”

Among the Persians a dualistic way of looking at things became prominent, and life was regarded as a warfare of good and evil. This religious dualism later worked its way to some extent into Christian thought. But viewed retrospectively, and despite the occasional appearance of dualism, the growth of the human mind is seen to be in large part a search for unity. Although in his superstitious days man was at best merely “feeling after” God, as we conceive of Him, yet the love of unity was evidently the implicit motive. Philosophy has been, for the most part, a quest of the same sort, that is, the search for a single rational principle by which to explain the most diverse phenomena. Religion would be impossible in the larger sense without faith in the unity of things. Science starts with the unity of nature as the great assumption which makes all her pursuits possible. The growth of thought has doubtless been hampered by certain presuppositions in favour of particular types of unity; and it is well to remind ourselves that our conceptions of unity are only conceptions. In a sense, the real proof of unity will be the attainment of that universal harmony of things which the mind puts before itself as the highest goal of our social life. Yet despite our philosophical failures, no endeavour is so inspiring as the persistent quest of unity, even in the face of facts which seem too varied to permit of unification into any system which the human mind can formulate.

The belief in a man-like creator, who wrought the world from outside in a few days, or creative epochs, then retired to watch over it, is one of the neatest illustrations of unitary belief. The earth was then supposed to be the centre of interest, and everything on it was said to be for man’s benefit. The unity was sometimes broken into by special creations and providences. Yet in the main the conception met men’s demands until their peace was rudely interrupted by the pioneers of modern science: Copernicus with his theory that the sun is the centre of things, and Giordano Bruno with his belief in the infinity of worlds. How great was the readjustment then required! How man fought for his position as the centre of creation, a contest which ended only with the nineteenth-century discovery that man is in every way a part of nature, one among many beings and greatly beholden to all that preceded his advent!

The argument from design in nature to the existence of a God of nature is another neat way of attaining unity. This is a way of approach to belief in God which will probably always appeal to the popular mind. Nothing seems clearer than the proof that, since evidences of intelligence are everywhere about us, there was a Creator prior to all adaptations and adjustments of means to ends. Yet such arguments have come to hold a subordinate place since the days of Kant’s searching analyses in his Critique of Pure Reason, and since the discoveries of Darwin. We are now aware that nature produces misfits, that purposeless organs survive, and that there is a far greater production of animal life than the world would have room for were there no sharp struggle for life. The same facts by which some people have sought to prove God’s goodness are by others taken to mean that God is cruel. It is doubtful if the facts of nature, considered by themselves, show conclusively what kind of being God is. Nature is as fertile as the Christian Bible in the suggestion of proofs.

Philosophically considered, nature is at best only a part, not the whole, of the ultimate system of things. Any argument based on natural facts must, then, be reconsidered from the larger point of view. Even the argument from the fact of evolution to the God of evolution may prove to be only a temporary expedient, although the law of evolution be made to include man’s mental life as well as his physical nature. For the conception of an abiding order, behind the flux of evolution, puts the whole relation of God to His universe in another light. The law of evolution must then be in some sense subordinate. Questions concerning the ultimate nature of that which evolves are more fundamental. Underlying those problems there is the still more fundamental issue, What is the ground whereon evolution appeared?

The attempt to answer this question might lead one to an entirely different approach to the conception of God.

Moreover, the great minds have given up trying to “prove” the existence of God. Such an attempt simply reveals the extreme limitations of finite thought. God is logically prior to all attempts to prove that He exists. He is historically prior to all discoveries in regard to His power, life, or causality. The universal evidence of belief in a Supreme Being as a living presence is far more conclusive than any argument, whether deductive or inductive. The consciousness, the experience commonly said to reveal the divine presence greatly exceeds the best report that is made of it. A poetic or suggestive account puts all logical arguments to shame. If we are ever to transcend anthropomorphism, we must make many allowances for the feeling factor, the immediacy. Arguments from the evidences of design in nature satisfy only while we regard life from a very limited point of view. God is far more than the “cause” of the world, else He could not be its cause. Nature is far more than an “effect” The category of causation is of minor importance.

It is well, however, to note that the argument from design fails because it is inadequate, not because it may not be in a measure true. When men set forth what they deem the divine “plan” they usually have in mind certain conclusions which they have read into nature and into human history. That is, after an event has happened, men very easily say that just that occurrence was “designed” to happen precisely when and as it did. Had we more wisdom, we might read something entirely different into our lives. Had we more insight still, we would be more likely to follow our superiors in wisdom up what Emerson calls “the stairway of surprise,” patiently waiting to see where that stairway leads. Time was when men ventured to reveal all the creative secrets of God, even to describe the topography of His attributes. Nowadays, men are becoming too wise to hazard a guess at what life is for, except so far as they find within themselves a certain power to live it, and to describe that life for the benefit of the race.

Another clear-cut conception of unity was that delectable sundering of society into two groups, “the elect” and “the damned” It was easy to posit predestination when it happened to be the other man who was condemned to seethe and boil. Probably the idea of a hell as neatly unified the world for those who found themselves relegated to it. It was easy for the Greeks to parcel off the world into citizens of their particular state, on the one hand, while all other tribes were classified as “barbarians.” The words sound glibly on our tongues by which we speak of a large part of the world as “heathen” and the rest as “Christian” It is equally pleasant to classify certain books as “profane,” one book as revealed. All this passes as unity until it occurs to us how terrible is our offence when we characterise the life of God with any of His people as “profane,” when we recollect that every human being owns God as Father. The shock is great, sometimes, whereby men are aroused into larger ways of thinking. They see that by their aristocratic belief in sin, evil, and the devil—for other people—they have impeached God. They learn at last that each soul counts for one only, and that the true unity of the race includes every member of it in one entirely liberal “City of God”

Popular optimism is another lightsome approach to belief in unity. Yet those who have sunk into the depths of pessimism, then have emerged into the conviction that the world may be made better, seem to possess profounder knowledge of life’s unity—an ideal unity for which each of us may and should heartily strive. The most satisfactory conception of unity must obviously have room for both the abiding and the changing, both the striving and the goal. If we are continually upset in our supposed security it is only because our hold upon unity was only an incident by the way. Most of us are compelled to supplement our theory of unity by a large addition of faith. As matter of fact, what we mean by unity is simply this: our present outlook upon the world from the point of view of faith. Even scientific men are beginning to confess that the scientific concept of the unity of nature is at best a device of our subjective consciousness, a shorthand account of our sensations.[1]

To turn from our Western way of thinking about nature as the field of “design,” system, order, to the prevailing Hindoo point of view, is to find that millions of people are satisfied with a way of thinking which flatly contradicts our own. To put nature under the ban of maya that is, the veil of man’s limitations and misapprehensions, seems to us to condemn nature unheard. Yet the Hindoo seers have found riches in the world of contemplation—shut out from all that we call most important—which are wholly unknown to the practical citizen of our Western world. It is not for us to condemn the reports of these mystical visions until we have sympathetically experimented in the same field. To think one’s self into the Buddhistic world, with its theory of “Karma” and “Nirvana,” its psychology without a soul, and its wheel of life, with no “real” that abides, seems to us to turn away from all that is rational. Yet, consider the beauty of conduct which the Buddha associated with his reactionary metaphysics; remember the priestcraft which he revolted from, and you will see how shortsighted is that criticism of his type of unity which emphasises its negative side.

We are inclined to take the freedom of the will for granted, or at least we accept some form of freedom as essential to faith in the moral order. But it is instructive to turn from this mode of thought to the world of Mohammedan fatalism, and try to understand the kind of unitary belief which that conception implies. Again, to believe with the Buddhist, in “Karma,” is to hold to a hard-and-fast scheme of things where there is said to be not a single deed which does not exactly conform to the law of cause and effect, a law which not only binds us, but which exemplifies the fruits of our conduct. No conception more easily aids the mind to rise to the thought of unity than the idea of law, natural or moral; yet none more quickly suggests our bondage to a kind of imprisoning fate. But nearly every way of thinking upon this basis has its exceptions. The theosophist who assures us that we are bound by the law of “Karma” immediately qualifies his statement by promising that when the soul learns the truth concerning the “wheel of life,” it thereby becomes free from the law of rebirth, with its attendant “Karma.” To find the ultimate theosophical unity of things, we must then look beyond the law of karmic cause and effect. The Christian believes that man will some time be a “law unto himself” Some of the great German philosophers taught that in this world of experience man is bound, yet in the transcendental world he is free. The ultimate unity, therefore, lies far beyond the domain of natural law.

The ordinary ethical way of regarding human life as essentially a moral experience seems to be an easy method of attaining the idea of unity, and many ethical philosophers are thoroughgoing monists. But what shall we say of nature in its premoral forms? If the moral ideal be a predetermined unity, there is no ground for morality at all; for the existence of alternatives, the liberty either to sin or to be righteous, is a necessary condition. If each of us has the possibility of moral action, then the so-called moral order is in some respects potential; it is a collection of individuals, not a unit. It is obviously necessary to distinguish between the possibility of that which is, and the ideal unity of that which ought to be. The belief in unity means that the cosmos is ultimately congruous with the moral ideal; our God is a God of righteousness, and the world of human society has the ideal possibility of becoming in very truth the moral republic of God. In other words, both freedom and righteousness are such large terms that we must take both present and future conduct into account, the actual and the ideal, the plurality of potentially moral individuals and the God whose constant guidance “makes for righteousness.” Moral unity is thus an ideal yet to be attained. It would be robbing ethics of its meaning to declare that the world is a unity now.

The assumption that all men are perfect now is perhaps the most indolent way of attaining unity, for it at once robs human life of much of its value. If we are perfect now, it is plainly useless to try to become any better; the world is in a static condition and has no reason for being, since existence adds nothing. We ought, then, to declare that the idea of progress is an absolute illusion, the entire world of error, sin, and evil is illusion; we are simply waking up to the fact that we were utterly deceived, and have never really overcome anything.

Almost as indolent is the theory that our experience is merely an evolution of that which was long ago involved. For the real value of life consists in achievements whereby each of us adds somewhat. If we are merely unfolding we are only machines, mechanical puppets for the amusement of some blase god. Such a theory is entirely in conflict with what we know about life, namely, that it is the domain of experiment, heroic struggle, and achievement. When we really consider it, this idea proves to be as barren as the idea of a goody-goody heaven where there is nothing to do except to walk about on the golden streets and sing psalms.

Far more acceptable are the little worlds which book after book creates for us, the realms of contemplation and feeling to which we are admitted by great poems, symphonies, pictures, and other products of fine art. Awed by the complexities of life, the average man adopts a practical conception of unity which alters day by day as experience demands. It is only now and then that we become dogmatic and assert that our particular creed unifies the world. Yet it is easy, when we do generalise, to fall into the illusion that our particular conception of unity is the truth of truths, not a private working hypothesis. We forget that there are millions of people on the earth who hold no such view, that we count for one only, while each of these others may have found as direct a road to the heart of things. What we condemn as “materialism” may not be such to the one who holds it, for we are apt to judge by appearances and by terms. The rationalist who disparages all mystics as fanatics may be condemning one-half of life’s reality; while the mystic who discounts reason may thereby defeat his entire object as a public teacher. The fatalist is not, strictly speaking, a fatalist; his conduct belies him.

The pessimist believes in an order of things where pessimism plays no part; otherwise he would not be a pessimist, for he could not condemn this world unless he knew a better. The sensationalist sees a wealth of reality in his chosen types of thought, or else he deserts his philosophy and adopts a practical point of view. One who is a philosophical materialist may be an ideal lover of his fellow-men, may be far more useful to society than a dozen transcendental idealists. It is probably true that no professed atheist ever was really an infidel. You must estimate a man’s conduct as well as his theory to find out what his real unity is. The hidden sentiments of a man’s life are most apt to show what he believes.

Religious creeds are usually the simplest formulas for the unity of the world. Religion is usually the resort when our conceptions are rudely upset by the unexpected. The higher the type of thought the more it tends toward unity, with the exception of a way of thinking which we shall consider later. But there is a unitary belief which is supposed to be a dreadful obstacle to this higher faith, namely, materialism. Yet no bugbear is more cowardly when we approach with confidence, none is more readily misinterpreted. The great conceptions of unity which we have to reckon with do not include materialism, but science in general, religion, man’s practical attitude as expressed in common sense, and the crowning science of human thought, constructive philosophy, the science which examines the presuppositions and compares the results of all other modes of thought. The great value of studying the types of unity is, therefore, to discover the various movements of human thought and learn their profoundest lessons. Hence it is important again and again to begin as far back as we can and note the vicissitudes of the unitary conceptions as they have been differentiated from man’s first beliefs.

In the theological transitions of the nineteenth century we have an excellent illustration of the transition from unity to unity. When the philosophy of evolution was brought forward it seemed to many that the very structure of theology was threatened. For if evolution is the law of production, what place could a creator fill? The arguments for the unity of nature are so strong, as presented by scientific evolutionists, that there seems to be no room left for God. Yet long ago it was evident that the theory of evolution was simply one more unity added to our rich heritage. Just as Copernicus compelled the world of thought to adjust itself to the larger conception of our solar system, so the philosophy of evolution called for an enlargement. Little by little men began to see that there was the greater need of a God, on this hypothesis. The old idea of a man-like Creator who finished His work in a week was only suited to man’s slight knowledge of nature. Meanwhile that knowledge far outstripped theology, and when theology came to consciousness there was great zeal to enlarge its scope. It was only in the heat of controversy that theology seemed to be the loser. For scientific evolutionism applies, as we have already noted, to certain phases of the universe only. The entire universe could not have been an evolution, with nothing to start with, no primeval force, life, or substance. Science believes in that other great unity, the law of the conservation of energy, even more than in the law of evolution. Whatever changes have come about in the physical universe, and whatever may result in the future, science assures us that the sum total of energy remains eternally the same. The law of change is subordinate to the law of conservation. The question still remains, What is that force, or life, out of whose activities all changes have come? What is eternal reality? What abides? For only when we pass beyond the thought of growth, change, and decay, do we reach the conception of that unity of unities without which our world-system could not be.

There are other considerations which show how foolish were men’s fears, when the theory of evolution seemed to threaten his belief in higher things. For even if evolution were the one great law, it would not prove itself such till every department in life had been explained. As matter of fact, evolution has thus far proved inadequate to account for that which it ought, first of all, to explain in order to justify its universality. That is, the origin of life is not accounted for; the transition from the inorganic to the organic kingdoms is still a mystery; and, most important of all, the origin of consciousness is unexplained—the presence of mind is an enigma. The truth, then, is that, granted the existence of an ultimate life, eternally conserved; granted “habit-forming tendencies,” factors to explain the great transitions from kingdom to kingdom, and, granted mind, evolution works very well. That is, evolution works within nature, on the one hand, and within consciousness, on the other. But when it is a question of the relationship of matter and life, of mind and brain, evolution falls back helpless.

Thus, human thought expands as rapidly as great men propose new types of unity for assimilation. There is momentary disturbance, then the new idea finds its place, and still there is room for larger generalisations. It is not improbable that science will be called upon to readjust all its theories in accordance with the discoveries of psychic research. F. W. H. Myers’s theory of the subliminal region may be the connecting link which will enable science to account for mysterious variations in human consciousness. But the mere suggestion of such a thing would now be ridiculed—so long does it take to learn the lesson of past readjustments. Such theories are usually branded “unscientific,” and at once rejected. Yet it was by the same painstaking method of exact research which distinguishes modern science, that Mr. Myers gradually developed the profound hypotheses of his great work on human personality.

It is sometimes argued that even telepathy is impossible, since it is inconsistent with what is known about the universe. Again, it is said that if mind affects matter in the least degree, or if matter influences mind, the law of conservation of energy is broken. But what if the law of conservation be an inadequate hypothesis, if limited to the physical world? There may be a larger unity of world-life which contains both physical force and mental activity. If we stop at the alleged chasm between mind and matter, our theory is still dualistic. Since mind and matter both exist in the same universe, there is obviously a greater unity which holds them both, and it is this world-unity which ultimately concerns us. The conception of the parallelism of mind and matter is a useful working hypothesis, but it is well to remember that it is an hypothesis.

There is, of course, great value in a relative conception of unity such as the scientific law of the conservation of physical energy. But it is still a conception simply, an hypothesis devised to account for one domain of human experience. The great men of science are free to confess that even evolution is a working conception. All scientific unities are subject to modification in the light of further knowledge; they are not understood to be absolute laws.

Yet, despite the fact that the point of view of evolution may not be universally adequate, it is important to remind ourselves how greatly the modern doctrine of evolution has enlarged our horizon. Formerly, the entire universe was held to be a finished product, while human souls, if not actually rated among the elect or the rejected, were supposed to be granted very meagre opportunities of regeneration, ere they entered a heaven or a hell where there was apparently to be no progress. Scientific accounts of evolution have now accustomed the mind to contemplate vast aeons of growth. Ten thousand years are but as a day, as men once reckoned time. No one now undertakes to limit human history except in a very general way. It is but a step from the past history of the earth to a conception of a vast future to which we may look forward as an indissoluble part of the present.

Opportunity is conceivably coextensive with time: opportunity is but another word for salvation. Thus the old fear passes over insensibly into a new trust, and anxiety gives place to equanimity. Zeal for future security from torment gives place to joy at the blessing of life as it passes. The old doctrine was founded on the necessity of immediate salvation, the new is inspired by faith in the everlasting integrity of things. Formerly, existence here was viewed as a fragment cut off from a boundless abyss of mystery in the past, separated from an uncertain eternity in the future. Now, life is viewed as a whole of which each day is an inseparable part. Life “here below” now flows: once it was a relentless measuring-rod to test men’s fitness to pass beyond it. The old order was dualism,—God and the devil at strife. The new is inspired by belief in a progressively attained unity.

Other believers in what is sometimes called “the higher philosophy of evolution” go farther and announce a new optimism. Whatever comes, so the advocate of this larger faith maintains, all calamities and hardships are advance agents of love. There may be many asides and counter-activities, but there is in truth no adversary. Evil and woe we have with us still, but they have changed their temper. Once we went forth as children. Now we go forth as men, confident of victory. There is not the slightest excuse for inaction, but it is action of another sort. There is no reason why we should get down in the dust and push, as if the universe might not arrive in time. There is no time-card in God’s universe. We can now afford to enjoy the scenery of the present moment, well assured that the landscape around the bend will still be there when our life-train arrives. There is a universal tide, pulsing, throbbing, pulsing, ever flowing forward, and on and on. That tide bears everything on its bosom; that stream is the stream of atom and of star, the pulse-beat of the Almighty. Infinite are the rills and whirls and eddies which checker its swelling tide. Numberless are the byplays of its passengers. A man may rage and tear and buffet it. He may idly float with its silent rhythms. Or his strong arms may carry him onward with its harmonious motion. But on he must go. Free, he is yet fated; fated only to be free. You may with the rebellious one, count life a warfare or with the apathetic deem it a bore. You may complain of its tantalising mystery, or rejoice with him who conquers. But the reality of realities you shall not see until you, too, move with and for the current.

Yet what numbers of profoundly thoughtful people there are in these days who either have not caught the spirit of this new optimism, or who still prefer to remain agnostics! This agnosticism is apt to pass, however, into dogmatism with the declaration that our knowledge is hopelessly relative, that reality is “unknowable”—what a strange word to apply to that which we know so much about! The unity of religion has been broken into, and in their doubt many good people have drifted from the churches into sects of greatly inferior persuasion. The liberalising movement of the nineteenth century has done its work and grown weary of its “pale negations” We are all heartily tired of negative critiques, yet how shall we transcend them? What shall reestablish centrality? What can be done to counteract the zeal for specialisation whereby modern knowledge is collected and catalogued faster than it can be unified?

Chapter II. Recent Tendencies

IF WE examine the tendencies of thought which mark the transition from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, we find three striking characteristics: the decay of faith in authoritative theology, the heightened development of physical science, and the growth of empirical or practical philosophy. The first tendency has long been viewed with alarm by devotees of religion. The unprecedented success of physical science has seemed to make for materialism, hence, to render the progress of religion the more difficult. The third tendency is often taken to be an indication of degeneracy. Thus, many have found it difficult either to retain their faith or tell whither our transition age is tending.

Now, it would be an enormous assumption for one man to claim that he could read all the signs of the times. It would be equally preposterous for him to undertake to unify the many diverse contributions of thought in an age of rapid multiplication of special sciences. The larger faith of the growing century will be the work of many minds of contrasted points of view. That faith must reach a certain degree of maturity before it can be unified. The process is the same in one’s own thinking. The intuition which unifies comes long after the analysis which sunders and the self-conscious logic that fails. Yet it is possible even while one is immersed in the process to see whither some of the lines of growth are tending. If one can but show that what seemed to be degeneration really is growth, one has accomplished something. Let us, then, try to interpret some of the signs of the times, with the understanding that even those signs are shifting while we study them, yet shifting to more and more promising fields.

For example, take the rapid division and subdivision of modern science, the unprecedented increase of knowledge beyond the capacity of great men to take account of it. Is it really cause for regret that we have few great men who stand out prominently above their fellows? Is the tendency toward specialisation to be deplored? Despite this tendency, the sum of unified knowledge is infinitely greater. There are many thousand times as many people who are skilled in science and literature as there were in the days when one man might know practically all that was worth knowing in his age. If no one genius can now lift himself prominently above the crowd, it may be because a thousand seers are about to co-operate to declare the greater revelation of our more social life. If we have fewer great poets and other men of universal genius, it may be because a yet greater truth is about to find expression through many minds, whose common message we shall presently understand—when we know the basis on which they are working. With the growth of trusts, socialisms, and other plans of unification, political and social problems multiply faster than any one thinker can take account of them. But this very complexity bears within it the seeds of its own simplification, and we shall presently discern its meaning.

Nothing is easier than to misunderstand, and no doctrine is more ignorantly put aside than materialism. The critics are usually those who have been subject to materialism in some form, and are at last free; and when a man is free the mere mention of his former burden is enough to call forth a torrent of abuse. At the least indication that an idea or a scheme is the work of his old foe, he is on the alert. When the critic of materialism has once labelled the new idea or scheme, that, of course, settles it: it is “materialism,” and there is nothing more to say. A little discriminative thinking would have shown him that no conclusion is more superficial; that a man is not really free from a thing until he has understood it.

To understand materialism, it is necessary to understand the reactions of the age. For many centuries man lived under the lash of dogmatic theology. He has been told, until he is tired of the very words, that he must save his soul and prepare for the future life. During the Middle Ages, he even believed that the body was evil; and there was but little in this beautiful world that was not condemned. Luther and his contemporaries won for man the right to reason, and after a time men of learning began to rediscover nature,— though a few isolated men, like Galileo, had already prepared the way by catching occasional glimpses of her wondrous beauty through Renaissance rifts in the theological clouds. Nature once more discovered, it was possible for man to rest for a time in his theological exercise, and take comfort in his body. Then came Darwin, Spencer, Huxley, Tyndall, and the rest, and the field was free. That scientific materialism should flourish for a while as never before was perfectly natural. Materialism had its first free opportunity to gather the scattered treasures of physical science which had never been unified since the days of the Greek atomists.

Philosophically, materialism arose rather late in human history, and had a shorter life than many systems. To be sure, one of the many Hindoo systems of philosophy was materialistic, but materialism could make little headway in the land of contemplation and spiritual pantheism. Not until the days of exact thought in ancient Greece did materialism really become a candidate for world-philosophy. Even then it had small recognition, and it was more than a thousand years before it became very prominent. The climax of its power came in the eighteenth century.[2] The rise of the philosophy of evolution gave the materialists new hope, but that hope was short-lived. By the middle of the nineteenth century scientific men began to be too wise to be materialists, and the only alternative for those who could not accept idealism was to become agnostics. Huxley summed up the changed attitude when he declared that he was not a materialist because he found himself “utterly incapable of conceiving, the existence of matter if there is no mind in which to picture that existence.”[3]

The great men of science to-day are not materialists. They are specialists whose particular assumptions and conclusions must be philosophically reexamined before their place in relation to what is real can be known. Those who declare that science is materialistic because the devotees of its various branches talk only of atoms, forces, masses, or other things, simply fail to understand. The tendency is towards a unitary conception of the cosmos whose one life must be sought beyond the mere presentations of sense.

Nowadays [says Ward][4] there is nothing science resents more indignantly than the imputation of materialism. For, after all, materialism is a philosophical dogma—it professes to start from the beginning, which science can never do, and, when it is true to itself, never attempts to do. Modern science is contented to ascertain coexistences and successions between facts of mind and facts of body.

Let us illustrate by the much-misunderstood physiological psychology of the day. It is easy to condemn it as materialistic, and go on one’s way rejoicing in the superiority of one’s spiritual knowledge. But this psychology does not pretend to be complete, any more than chemistry is a complete theory of the universe. It has a very limited purpose, namely, to learn all that can be known about the mind from one logically defined point of view, namely, when the mind is studied in connection with brain states.[5] Enough has been learned already to justify all the time and labour. If hard-and-fast limits shall some time be discovered, spiritual psychology will immensely

profit thereby. At the lowest estimate, our knowledge of a human being will be greatly increased. Let the work go on, then. The psychologists are endeavouring to make of psychology a special empirical science in which one may study conscious states as such, without regard to values, or ultimates. The same man who is a physiological psychologist is also a human being, and if you follow him through his day you will find that there is much to him besides his psychology. He may, for example, very frankly tell you that all questions of worth or value must be referred to ethics or to philosophy in general. He is far from measuring the world by his special science. Likewise with many other scientific men classified as materialists. To know what they believe as men is to have this superficial judgment entirely removed.

For example, Professor Munsterberg, of Harvard, would naturally be singled out as the most materialistic of these new psychologists. But it happens that philosophically Professor Munsterberg is an idealist of the Fichtean type. That is, he believes that the results of his special science must, like the data of any other science, be philosophically reconsidered and described in terms of the self. This alleged archbishop of materialism, then, holds that the true view of life is the reverse of the materialism with which he is credited.

Again, take the popular materialism of the day. In the truest sense it is the glad joy of man in unhampered existence in the physical world. When one considers the bondage which he has thrown off, it is plain that, on the whole, man has behaved very well. It is the first time in what is called Christian civilisation that he has had liberty to study and develop the resources of the visible world. He is now trying the materialistic hypothesis to see what there is in it. Stand aside and see what he will do, how far he will go. If he is a bit extreme for a time, never mind; the only way to know that it is an extreme is to try it. This is the age of scientific invention, discovery, and development. Man is now building the foundations broad and deep for a larger, higher life. I make bold to say that there is more that is sound, rational, enduring, yes, spiritual, in this kind of thought and life than in any of the ages when man has condemned matter and tried to make himself spiritual by asceticism and other exclusive methods. Amidst all this commercialism and love of luxury there is more that is sound and sweet than in any age of the world. There have been greater seers than any now living. There have been little groups of more spiritual people, but never such a general diffusion of sound sense, of rational belief in law, order, justice, peace, the unity of life. The present-day scientific man who claims to know nothing about God knows more about Him than the theologian of the past, who thought he knew God well enough to catalogue the divine virtues. To be sure, there are some who are greater materialists to-day, because there is greater acquaintance with matter,—for example, many exponents of medical science. There are those whose noses and eyes are buried in matter, and who see naught else. But these are few. The general trend of the age is far different.

This is, of course, no argument for materialism in its debasing forms. There are tendencies in our age which are naturally observed with deep concern. But the present play on the stage is the drama of physical life. When the crowd is tired of the play there will be a change, and, note this, when this play has had its run we shall know something. It is no half-way affair, this time. We are really in earnest to find out what there is in the visible universe. We may say unqualifiedly that until man had tried the experiment he never would have been satisfied. If, later, he turns to the invisible world with new zest, it will be to hold fast as never in the history of the world. At any rate we must pass through the period and have done with it. It is barely possible that by having the experience we shall learn so much that many of our views of the invisible will be greatly broadened.

Many of the materialistic tendencies of the time which we deplore will run themselves out in due course. We can well afford to let this transition period show what it is to lead to before we cry out that human nature is degenerating, or that the great social problems are past solution. The fact that religion is seeking new forms of expression is not alarming to those who value the spirit rather than the letter. The bare negations of agnosticism do not long satisfy either the scientist or the man of religion. The age demands the truth which the negations hide, and many labourers are earnestly working in the constructive field to meet just this demand.

Many substitutes have been offered for old faiths, but they have been mostly ephemeral and extreme reactions from outworn creeds; and reactions do not long meet human needs. There has been an outbreak of fads and catchpenny schemes. But the fact that these schemes have won temporary acceptance simply shows that the people are restless. The old dogmas have been brought out, dusted, and repainted. But the veneer was so thin that only the unprogressive were held by the device. We have had cries of “Back to Nature!” “Back to Kant!” “Back to Christ!” Yet no mere return to any faith or any person will suffice. When people begin to doubt, the only resource is to resolve the doubts. If history reappears in a new light, well and good. But we must first have the light.

The profound interest in thoroughgoing philosophy which so many manifest in our day is undoubtedly the most direct evidence of the pathway to unity. The special sciences leave our knowledge in fragmentary shape only because their presuppositions have not been searchingly examined. Agnosticism has held sway only while men paused by the roadside. Behind even the most negative critiques there is a wealth of positive wisdom which a profounder analysis would reveal. If our sense of unity has been disturbed, it is because we are called upon to assimilate this profounder wisdom. It was first necessary to criticise the old beliefs in order to get things in motion. But close upon the heels of the retreating scepticism of our transition age a new conviction is coming. The optimism of the “higher philosophy of evolution” already expresses this conviction in part.

Another indication that a larger faith is taking shape is the gradual transition of Christian thought from the old theological basis to a philosophical foundation akin to transcendental idealism. Typical of this kind of thinking is

The Philosophy of the Christian Religion,[6] by Principal Fairbairn, of Mansfield College, Oxford. A brief outline of the book will give a clue to this transitional thinking.

Instead of starting with an abstract premise in the ancient fashion, the author starts with nature, and asks whether nature is self-explanatory. Naturally he finds it necessary to look beyond the physical world to find a basis for nature, for man, and for the personality of Christ. This basis he finds not in the supernatural world in the old sense, but in the transcendental world of God, the eternal reality whose power is the immanent life of the great universe which reveals Him. In nature and man he finds reason, order, signs of intelligence. The energy of nature is the correlate of freedom in man. Man is the interpreter of nature. Since both nature and man are rational, there must be one rational constitution in each, one intelligence in both. The noumenal, then, not the phenomenal, explains man. Evolution is not self-explanatory; it does not account for the appearance of mind. Nature cannot be conceived apart from ultimate reality. But, once in possession of a philosophical basis of that which lies beyond the merely natural, why may we not find room for a higher Person, the Saviour of men?

In the same way, the author pleads for a larger interpretation of history. To the historical argument, he adds the argument from ethics, the problem of evil, the philosophy of religion; and the great fact that man is a religious being,—that no theory can account for him which leaves his religious nature out of account.

The second book is an elaborate consideration of the personality of Christ, the relation ofJudaism to Christianity, the results of the higher criticism, the contributions of the apostolic writings to the Christ idea, and the gradual development of this idea. The Christian religion was not built on Jesus of Nazareth, but upon the idea that he was the Christ, the Son of God. It is the understanding of what lies within this idea which explains the unparalleled fact of the Christian religion. It was the power of the Person, not merely what he said and did. The cross was essential to that idea, yet it was the being who passed through the crucifixion from whom the great power was sent out into the world.

The Unitarian might complain that the author occupies a compromise position; that it will require another fifty years for writers of this stamp to be completely emancipated from the old theology. But one is inclined rather to credit the volume for what it is as a fine piece of transitional thinking. Other critics might say that a fully worked-out philosophy must more carefully consider the question, What is reality? and must defend itself against the attacks of pantheism and other mystical doctrines. But this criticism has been exceptionally well done in another noteworthy work, which is far more indicative of the tendencies of the times.

Without doubt the most important philosophical work issued in recent years is The World and the Individual,[7] by Professor Josiah Royce. The general purpose of this great work is the development of a theory of first principles as the basis of a philosophy of religion. The first series is devoted to the doctrine of reality, the second is concerned with the relationships of God and man, man and nature, the meaning of evil, and the nature of the moral order. In the first series there is a critical and historical examination of the leading types of theories of reality, while the second is largely devoted to the more detailed exposition of Professor Royce’s particular views. Realism and mysticism have perhaps never received more searching criticism. The positive results of these doctrines are carried over into what Professor Royce calls “the fourth conception of Being,” a form of constructive idealism which, profiting by the exercises of post-Kantian thought, finds a method of assimilating the more rational results of the foregoing conceptions.

The theory in general is through and through teleological. The temporal world is, from first to last, a world of purposes. Time is the form of the will.

Nature is so far real as it fulfils a purpose. For the Absolute this purpose is at once one and many: one, as the eternal, unitary basis of all existence; many, as at once the temporal working out of the eternal unity and the varied wills of finite individuals. The finite self is at once determined and free—determined in so far as organically related to other selves and to the Absolute, as a moral individual; and free in the strictly ethical sense, as a temporal agent reacting upon the diversified presentations to which the will gives attention. The unity of the one and the many is thus a unity of wills. What is incomplete in the temporal order is fulfilled in the eternal. Sin is due to ignorance of our true selfhood, and evil is finally overcome by good. The doctrine is thus essentially different from mysticism, since nature is purposive: it is not pantheistic, since it finds room for genuine finite selves, and goes far toward meeting the demands of pluralism, while not sacrificing the unity of the whole.

The criticism which this work has received shows that the theory is still incomplete. The present reference to it should not by any means be taken as an endorsement of all it contains, leastwise of its theory of the Absolute, and its negative critique of mysticism. But it is one of the signs of the times; and the great interest which it has aroused is one more evidence that it is constructive idealism, thoroughgoing philosophy, which is to furnish the true basis of unity of modern thought.

Of great consequence, too, is the tendency toward empirical philosophy under the leadership of Prof. William James, one of the most influential thinkers of our day. If ever there was a disturber of the unities of thought in which dogmatism serenely takes refuge, it is this champion of the facts that are left over after the system-makers have done their work, Few books have done so much to call attention to the neglected factors of life and thought as The Will to Believe. Professor James even dares to question the monistic hypothesis itself. He is far more interested in fidelity to life, with all its heights and depths, than in the consistent carrying out of some pet logical hypothesis which may perchance leave half the world unexplained.

To some his strictures might seem even more negative than agnosticism itself. Professor James has nowhere worked out his empiricism into a connected system. But underneath the apparent negations one detects a belief in the unity of experience which is of profound practical significance.

In the works of such men the practical tendency of our age unites with the endeavour to develop a philosophy of pure experience. It is precisely this new empiricism which is rising to meet the demands for a new spiritual awakening. It is living experience which supplies the lack which speculative philosophy feels. The appeal to practical experience is coming to be regarded as the final test of the validity of the larger philosophy to which the constructive idealists are now giving shape.

The demand that philosophy shall be practical, concrete, social, religious, is thus the profoundest demand of our age. This empirical demand is the surest sign of all that philosophy is again turning into constructive pathways. “Back to Experience!” is therefore the most promising of these modern cries. Reality still exists. God still lives. Life is still before us. We know not what wealth of experience may yet come. Life is truly worth living; there is really something to strive for, something to add to the great totality. Therefore reverence your present experience, be true to all the demands of instinct, reason, faith, and at the same time respect the lessons of history. If philosophy have not yet discovered the true unity, it is only because the wealth of individualisms is too great to encompass.

In the light of the new demands of the age, we may therefore say: If it be your purpose to interpret life, you must study and describe actual life as it is, as immediately presented; not begin with a logical fragment as your abstract premise, then deny the rest admittance because it is not logical. If nature is a part of a world-order which includes mind and the moral life as only in part realised in this physical existence, you should not expect to understand nature alone. If man is really an immortal soul, even now dwelling in eternity, you ought to take his spiritual character into account, not complain that as a physical organism he is unintelligible. The way to end with God is to begin with Him. Our premises must be as large as our conclusions. We should not expect God to break in somewhere into our logical abstractions, nor find the soul hidden away in the meshes of the brain. The problem of evil will be a mystery to the end if we continue to look in the darkness for a solution. The “heathen” will always be condemned as heathen until we start with the premise that every human being is a son of God in the kingdom of infinite love.

One might say that what the world most needs at present is to brush away all abstractions, and return to the sources of things until it is once more fired by the presence of the divine, until it knows for a fact that God lives; then be true to that fact, live for that fact, realise that the divine order is, exists,— not merely seems to be. It is not so much “reasons for believing” that we need as that type of conduct which accompanies thrilling belief, stirring consciousness of the divine. The world needs science; it needs education, thought, thoroughgoing philosophy, not mere dabbling in the metaphysical realm. But it needs the Spirit even more than it needs downright thinking.

We are absorbed in forms: let us have the Spirit itself. Therefore, when you read the imperfect terms of a philosophical book, remember the broadly spiritual ideal. Instead of singling out its defects and publishing them, set a new fashion and begin to be constructive; supply in your conduct what the book lacks. One must be tremendously in earnest to know life. One must courageously persist to the end. The science of truth is inseparable from the art of life, and one can no more float easily into the harbour of wisdom than one can know what love is by delegating some one to love in one’s stead.

Let philosophy become religion once more. Let religion be purged by philosophy. Let us begin work at last. We have scarcely reached the age of reason. We live in bits, in schemes, devices, and shadows, which we mistake for wholes and realities. Let us come out into the broad sunlight and be men. A man is an organic assemblage, and must be poet, philosopher, lover, and much else, all in one. The highest life is many-sided. We must adore it from many points of view. We must be beautiful in order truly to adore. Therefore, let us begin to live.

It is usual for philosophical discussions to begin with a lengthy argument for an abstract logical premise or with certain cardinal facts in the physical world. If we ought rather to begin with experience in its presented fulness we should plunge into the study of life where our own liveliest interests inspire us. These interests are apt to be religious or practical rather than logical. It is our higher nature which we wish to understand and preserve. We are not content with a soul which is condemned at the outset; with a God who is mentioned by way of apology at the close. It is time, then, to protest against that procedure which starts with the lower order of life, and ends by confessing that it finds no need of anything higher, or finds the lower itself a mystery. The procedure ought rather to be the reverse. The lower is only intelligible in the light of the higher. The attainments, not its physical conditions and origins, are the clues to evolution. The full-grown tree explains the seed, not the seed the tree. If our theory of nature’s unity is broken into by what is sometimes called “the supernatural,” we must reconstruct our concept so as to provide for the supernatural. If man is a spiritual being, a son of God, here and now, it is futile to try to understand him in purely physiological terms. Moreover, if he be an immortal soul, man ought to act as a soul, as a son of God, not as a creature of flesh and blood. Thus, practically and philosophically, the true clue to unity seems to be an entirely different method from that pursued by modern science. Science has tried to explain men by studying origins, the low levels of organic evolution. But more important than the question of origins is the problem of values, ends. To start with nature as a mechanical, self-evolving order is to end with the lower or mechanical unity. The origin of life and the presence of consciousness will always be mysteries until, beginning with man as a conscious being and with the universe as a living organism, we explain the mechanical by the biological, the biological by the conscious, and the human by the divine.

Thus the meaning of the present disturbance in the world of thought is the wresting of interest away from the mechanical and putting it upon the divine. Our age is witnessing a new movement towards belief in the higher order of things. We are learning anew that we are living souls. We are turning from abstract theology to the concrete God. And in this vitally absorbing, progressive present we are once more finding the pathway to the Spirit, the clue to the meaning of life.

Chapter III. A New Study of Religion

The WORKS of no living writer more sharply challenge criticism, and at the same time arouse admiration and zeal for intellectual growth, than the writings of Professor James, of Harvard University. For he is rather the critic of all points of view than the adherent of any one school. He is at once psychologist, preacher, friend, sceptic, and believer, ready to champion any new cause, yet admirably conservative when asked for an avowal of opinion. One is sure to agree with him at many points, but as sure to find him unsatisfactory in other respects. He is ever in pursuit of a larger theory, ever emphasising possibilities of which the ordinary man does not dream. It was to be expected that when such a man took up the study of religion he would have something strikingly original to say. It is safe to predict for his recently published Gifford Lectures,[8] delivered at Edinburgh University, 1901-1902, a popularity which will greatly stimulate interest in religion, and help to bring about the much-looked-for revival.

Instead of starting with an abstract premise in regard to the perfection of the divine nature, or indulging in abstruse reasoning with the intent to prove something, Professor James begins with real life. Believing that life comes before theory, he permits life as far as possible to speak for itself, and reserves his comments for the last. He has collected a large number of original documents, besides ranging through the entire literature of the Christian ages. To a large extent he considers the extreme types of religious life, well assured that if he gives place to the extremes all else will be included. The result is a mass of evidence in favour of religion which might well serve as a mine of wealth for religious teachers. It is seldom that the spiritual life is so effectively made to speak for itself.

In the first place, the ground is cleared by sweeping away medical materialism, which discounts religion by describing the disordered physical condition of religious people. It is just such temperaments which Professor James finds to be the most striking cases of religion. To describe the pathological condition is one thing, to evaluate the spiritual experience associated with it is quite another. Paul’s vision on the road to Damascus may have been a “discharging lesion of the occipital cortex,” St. Teresa may have been an hysteric, and St. Francis an hereditary degenerate; but that throws no light on the religious worth of their lives; that does not disprove the value of the spiritual revelations of these saints. For all that medical materialism can tell us to the contrary, the neurotic temperament may be the instrument for the production and growth of religion. It is not a question of description of physiological states, not a question of origin, but of values and outcomes. “By their fruits ye shall know them.” That which works best on the whole is to decide. Accordingly, Professor James devotes several chapters to the various states, fruits, and values of saintliness, and intersperses his analyses of asceticism and the like with delightful little sermons apropos of modern life.

Again, our author considers religion only in the personal sense. For him the real thing is the personal feeling, the individual deed, or reaction. Creeds, forms, institutions, are of secondary worth. The true religionist prays, puts love, passion into his life. His formulated statement comes afterward, and is frequently a lifeless crystallisation. There is no one religious essence, no specific or peculiar sentiment to which any given devotee can lay claim. This conclusion naturally leads to a pronounced individualism. Professor James welcomes the religious life wherever he finds it. He is not a mere Christian, but professes fondness for Buddhistic doctrines, and does not believe in evangelical imperialism.

The broadest possible definition is given to religion, with the reservation that it shall mean something sacred and ennobling, a higher kind of happiness, belief in the presence of a spiritual order. That is, religion consists in individual feelings, acts, and experiences associated with whatever men deem the divine. It is belief in the reality of the unseen regarded as a higher order, and may be associated with a wide diversity of content. The objective presence may not be there precisely as man conceives it. But, generally speaking, there is some sort of solemnly emotional or other aspiring attitude connected with this belief. It is the vast variety of these personal associations which forms the subject-matter of the psychology of religion, and the search is for an hypothesis which shall account for the experience on its human side.

The first spiritual type considered is the religion of healthy-mindedness, that is, the optimistic type. Then follows “the sick soul,” the conflict of selves, and an elaborate study of conversion, an analysis of saintliness, the limitations of sainthood, the worth of mysticism and of rational religion. In all these classes of experience, passed successively in review, the author finds value, authority, yet none is universal, none has commanded universal assent. The result is a powerful argument for open-minded many-sidedness. Even with all these types before us, it doth not yet appear what man shall be. There may be other modes of existence and other types of consciousness. Investigations like those of the Society for Psychical Research have opened a wide field of which we know but little as yet. One ought, therefore, to suspend judgment, to continue to accumulate data, and maintain the experimental attitude.

Professor James is not yet convinced of the reality of spirit-return, though he expresses great admiration for the work of Myers, Hodgson, and Hyslop.

He believes, however, that it is through psychical-research channels that we are to find evidences of immortality. The possibilities are great, but the facts are few as yet. It is well to leave the question of immortality an open one, and concern ourselves with the more immediate application of Myers’s hypothesis of the subliminal self. For it is this hypothesis which supplies the essential basis for the explanation of conversion and other religious phenomena. The application of this hypothesis is briefly as follows:

The study of mysticism and conversion shows conclusively that there is a deep reality in these experiences for the subjects of them. Whatever the creed, and whatever the idea of God, there are evidently forces outside of the conscious individual which bring redemption into his life. Whether occurring suddenly, or as a slowly matured result, a changed life follows a spiritual awakening. The old interests wane, the conduct of life alters, and a life of devotion takes the place of the life of sin and selfishness. This process of regeneration is describable in mechanical terms as a change in the centre of equilibrium. The change of heart, the awakened centre of spiritual feeling, possesses dynamic power. God, or some other exalted person, may or may not correspond to the psychological state. The human fact is that the change of mind and heart occurs in response to an experience which stands for the divine. The attention is transferred from the old life with its interests, from selfishness and the rest, to a higher centre of interest. Around this new centre of mind and heart, corresponding changes in the general mode of conduct group themselves. The subconscious mental life also responds. In fact, the change is largely subconscious at first. For it is in this larger mental life, active below the threshold, that the soul lies open to the unseen order, belief in which is the very basis of religion.

Psychologically, this means that a person who is religiously very impressionable possesses a large subliminal region. This subconscious field may open into the world of the divine, the realm of spirits, possibly spirit- return: its limits no one knows. The chief point is that Myers’s theory of the subliminal self supplies the basis for a complete psychology of religion, a perfectly definite theory of conversion.

All the voices that are heard, the visions that are seen, and the uplifts of heart and will are directly or indirectly gifts of this larger world to which every soul lies open. From a person’s subliminal self this larger world extends out on every hand to the unfathomed depths and unmeasured heights of eternity. Let us repeat: the voices may or may not be objectively real, spirits may or may not be present. But whatever the reality lying beyond, here at any rate, is the channel of communication. Here, too, psychology and religion are at one, for both admit the existence of a larger spiritual world. Professor James does not exclude one fact that it is dear to the religionist. The divine grace may be operative, supernatural experiences may occur, and all that is most precious to believers in the reality of sudden conversion. The author is not dogmatic at any point. He leaves room for the utmost freedom of opinion in regard to the nature of the Beyond. The point is that the whole experience is lifted from the plane of the superstitious and the miraculous, and put on an exact scientific basis of psychological law. The subliminal field of consciousness is the centre of interest, and here many diverse thinkers may unite.

Professor James does not see why Methodists should object to such a view.